The Sad, Strange, and Ineffective Story of the Canadian Firearms Registry

James Swan 05.02.13

The recent mass shootings in Connecticut and Colorado have stirred considerable discussion and action about gun laws, as well as boosting firearms sales. A rush to action is often not the wisest move on such a complex subject, for as criminologist Dr. Gary Mauser of Vancouver, British Columbia observes, “gun laws are typically passed during periods of fear and/or political instability,” which leads to “the slippery slope of gun control,” which is based on emotional reactions rather than solid research.

Dr. Mauser holds joint U.S. and Canadian citizenship and has taught at Simon Fraser for some 35 years. He has lectured all across North America, New Zealand, Australia, and Europe and published numerous papers on firearms. He has served as a Member of the Canadian national Firearms Advisory Committee, Ministry of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, and been a member of the advisory group to the Canadian delegation to the United Nations on Small Arms and Light Weapons.

Gary and I met at an international firearms scholars symposium that was held at the Tower of London in 2003, which was sponsored by the World Forum on the Future of Sport Shooting Activities. My son and I filmed a documentary about the symposium, A Question of Balance, which you can learn more about here.

A history of gun control in Canada

According to Dr. Mauser, historically Canada has had stricter gun control legislation than the U.S., lower rates of criminal violence, and a higher rate of suicide. In 1913, a fear of immigrants prompted the first national serious handgun legislation, requiring civilians to obtain a police-issued permit to acquire or carry handguns. Non-British immigrants found it difficult to get a permit.

In 1934, fearing labor unrest as well as American rum-runners, Ottawa mandated handgun registration that created separate permits for British subjects and everyone else. In 1941, concerned about possible Japanese sabotage, the government prohibited all “Orientals” (including Chinese) from owning firearms. This was ironic, as China was a wartime ally of Canada.

Canada had a gun registry during the Second World War, when all people were compelled to register their firearms out of fear of enemy subversion. This registry in Canada was discontinued after the war; however, all handguns continued to be restricted. Handguns are classified as “restricted weapons,” and so must be registered and are tightly controlled–they can only be taken to the range for example.

Terrorism in Quebec in the 1960s and 70s spurred Ottawa to limit handgun permits for “protection” to a handful of people, such as retired police, judges, geologists, and prospectors.

In 1977, a Firearms Acquisition Certificate (FAC) was introduced as a requirement to obtain ordinary rifles and shotguns. Gary Mauser notes: “The police decided to refuse an FAC to anyone who indicated a desire for self-protection. This is shocking given that in a typical year, tens of thousands of Canadians use firearms to protect themselves or their families, mostly from wildlife.”

The 1989 École Polytechnique massacre in Montreal prompted the Mulroney government to introduce Bill C-17 in 1991, prohibiting a large number of rifles and shotguns with certain cosmetic features. FAC applicants were now required to provide a photograph and references, take a 35-question test, and to submit to police screening. Vetting typically involved telephone checks with neighbors and spouses or ex-spouses. There was also a mandatory 28-day waiting period.

In 1993, the Liberals passed Bill C-68, which in 1995 became the Firearms Act. Over half of all registered handguns in Canada were suddenly prohibited, and plans were initiated to confiscate them. No evidence was provided that these handguns had been misused. The Auditor General found that no evaluation of the 1991 Act had ever been undertaken.

The heart of the Firearms Act is licensing. Owning a firearm, an ordinary rifle, or shotgun became a criminal offence for those who do not hold a valid license. Firearm owners and users in Canada must have firearms licenses for the class of firearms in their possession. A license issued under Canada’s Firearms Act is different from a provincial hunting license. Firearms licenses for individuals aged 18 years or older must be renewed every five years. “The instant it expires, if you still have your guns, you are a criminal,” Dr. Mauser advises.

Background checks are a big issue in the U.S. today. In Canada, according to the Firearms Act, a person cannot hold a FAC if the ownership of a firearm, prohibited or restricted weapon, crossbow, ammunition, and so on would put the safety of that person or any other at risk. Conditions under this clause include any person who in the last five years has been convicted or discharged of the commission of a crime; has been treated for mental illness associated with violence or the threat of violence; or has a history of violence behavior or threatening violent behavior.

In addition, the 1995 law broadened police powers of search and seizure, and expanded the types of officials who could make use of such powers, and weakened constitutionally-protected rights against self-incrimination. To coincide with the “National Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence against Women,” the Firearms Act became law on December 5, 1995.

The Canadian Firearms Centre was established in 1996 to oversee the administration of its measures. However, it took until 1998 to issue licenses and require buyers to register long guns. In 2001, all gun owners were required to have a license and, by 2003, all had to register all of their rifles and shotguns. At best, only 60 percent of all long guns were ever registered.

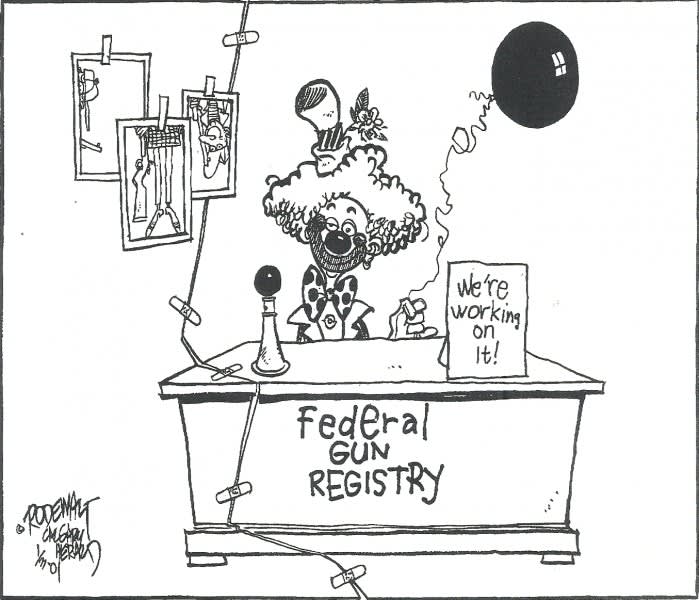

The Canadian Firearms Registry was managed by the Canadian Firearms Program of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). The net annual operating cost of the program, originally estimated to be $2 million (Canadian), instead rose to at least $20 million a year, and it was reported to cost $66.4 million for the 2010-2011 fiscal year. Notwithstanding an estimated $2 billion cost to date, the firearms registry remains notably incomplete and has an error rate that is embarrassingly high.

Effects, or lack thereof

According to Dr. Mauser, “In 1995, the government assumed that, by controlling the availability of firearms, the registry would reduce total criminal violence, not just gun violence, suicide and domestic abuse. This legislation was fundamentally flawed because it relied upon public health research to justify its moralistic approach to firearms. Public health advocates regularly exaggerate the danger of citizens owning firearms through pseudoscientific research methods. There is no evidence to support that the registry has had any influence on homicide, suicide, or domestic violence. A case in point is that while suicide by gun did drop during the registry, overall suicide rates increased.”

Even though the registry was created by the 1995 legislation, it was not implemented until 1998. Dr Mauser’s researcher found that, “Since the registry, with its dual function of licensing owners and registering long arms, was first implemented, the total homicide rate actually increased by 9 percent. Perhaps the most striking change is that gang-related homicides have increased substantially–almost doubling between 1998 and 2005. No persuasive link has been found between the firearm registry and any of these changes. The bottom line is that people who register their guns are less likely to commit crime, and criminals are not likely to register their guns.”

No convincing empirical evidence can be found that the firearm program has improved public safety. Violent crime and suicide rates remain virtually unchanged despite the nearly unlimited annual budgets during the first seven years of the firearms registry. Despite the drop in firearm-related suicides since the registry began, an increase in suicides involving hanging has nearly cancelled out the drop in firearm suicides.

Some highlights of the dismal record of the Firearms Registry:

- Law-abiding gun owners are less likely to commit homicide than other Canadians. Licensed gun owners have a homicide rate of .60 per 100,000 licensed gun owners between 1997 and 2010. Over the same period the overall homicide rate was 1.85 per 100,000. people Thus, Canadians who have a firearms license are less than one-third as likely to commit murder as other Canadians. As is the case with the U.S., knives are more likely to be used to commit spousal homicides than guns.

- The police never have shown the value of the registry. Police recover registered long guns in only two percent of all homicides. Statistics finds that only 4.9 percent of all homicides involved registered long guns. The RCMP has no example of the registry helping solve a crime.

On October 25, 2011, the government introduced Bill C-19, legislation to scrap the Canadian Firearms Registry. The bill would repeal the requirement to register non-restricted firearms (long guns) and mandate the destruction of all records pertaining to the registration of long guns currently contained in the Canadian Firearms Registry and under the control of the chief firearms officers. The bill passed second reading in the House of Commons (156 to 123).

On February 15, 2012, Bill C-19 was passed in the House of Commons (159 to 130) with support from the Conservatives and two NDP MPs. On April 4, 2012, Bill C-19 passed third reading in the Senate by a vote of 50-27 and received royal assent from the Governor General on April 5. As of 2012, the Canadian Firearms Program recorded a total of 1,889,650 valid firearms licenses, which is roughly 5.5 percent of the Canadian population . The four most licensed provinces were, in order, Ontario, Quebec, Alberta, and British Columbia.

Comparative control

“There are almost as many long guns per capita as in the U.S.,” Dr. Mauser told me, “but virtually no legal handguns. Canada has a large hunting community but no tradition of gun use in self-defense. Of course, there are criminals.”

In contrast, according to the General Social Survey the U.S. household gun ownership rate has fallen from an average of 50 percent in the 1970s to 49 percent in the 1980s, 43 percent in the 1990s and 35 percent in the 2000s, however other polls place gun ownership to be over 50 percent of the households. And, as these are voluntary polls, it seems likely that some people who do own own guns are not reporting them. Gunpolicy.org estimates that there are at least 310 million guns in the U.S., and over 88.8 firearms per 100 people, which is the highest rate of private gun ownership in the world. In the area where I live in New Mexico, police estimate that 80 percent of the homes own at least one gun.

I asked Dr. Mauser to compare gun crime in the U.S. and Canada. He replied: “In general, Canadian gun crimes and total murder stats are lower than the U.S., but our big cities have much higher crime rates than the rest of the country. This is except for the aboriginals in the prairie provinces where there are major problems with alcohol, minor violence, spousal abuse, TB, and child molestation. Most of the prairie provinces have higher violence and murder rates than the border U.S. states, for example Manitoba vs. North Dakota, or Alberta vs. Montana. And there’s more guns in those U.S. states than in those provinces.”

Mauser continued, “No solid evidence can be found linking Canadian gun laws to declines in either violent crime rates or suicide rates. Firearms have been persistently involved in about one-third of homicides since 1975. Canadian homicide rates fell 22 percent between 1990 and 1998, before the beginning of firearm licensing and registration, but slid just two percent between 1998 and 2009. In contrast, homicide rates in the US fell 33 percent between 1990 and 1998 and 20 percent between 1998 and 2009. Suicides involving firearms started declining before the 1995 law came into effect, falling from 1,110 in 1991 to 818 in 1998. After licensing and long gun registration became mandatory in 1998, suicides continued to fall, dropping to 534 in 2007 (the most recent data available). Unfortunately, total suicides have remained relatively constant (3,593 in 1991; 3,613 in 2007), as alternative suicide methods remain readily accessible.

The safety culture may have gone too far as society has become frightened by what formerly was normal firearms usage. Hunters have been charged with ‘unsafe storage’ when carrying unloaded firearms on hunting trips, high school students have been charged for merely carrying a BB gun, and widows are harassed by police attempting to confiscate their deceased husband’s firearm. Even though defending oneself against criminal attack is legal, legitimate defensive uses of firearms routinely result in charges of ‘possessing a weapon for a purpose dangerous to public peace,’ assault with a weapon, or even murder.”

In an earlier article I looked at gun ownership in Switzerland, where shooting is the national sport and people openly carry rifles about on buses and public streets. Mauser’s extensive research on Canada is but one more example that guns themselves are not the problem, but rather human behavior.

Dr. Mauser will soon be publishing a book, Misfire: The Failure of Canadian Gun Laws. It bears careful study. To see him interviewed on gun control on video, click here.

Note to U.S. hunters: while the long gun registry is gone, along with its data, today, if you want to bring a firearm into Canada, you still must acquire a firearms license on entry. An individual must be at least 18 years old to bring a firearm into Canada. If you are younger than 18, you may use a firearm in certain circumstances, but an adult must remain present and responsible for the firearm. And while you are out hunting, you must carry both the hunting license and the firearms license.