The BAREBOW! Chronicles: Moon Over My Antlers

Dennis Dunn 06.01.15

Silhouetted against a clear blue sky, perhaps two miles away and 2,500 feet above us, were two sets of caribou antlers. One dwarfed the other. Indeed, had the larger one not been so very tall and massive, my naked eye would probably never have noticed them there on the skyline at all without the aid of binoculars.

They were in the saddle of a high shoulder-ridge near the summit of what my guide, Gerald Buyck, had referred to as Castle Peak. Gerald and I were on a grizzly bear hunt together—hunting from a cabin on Elliot Lake, deep in the wilderness of Canada’s Yukon Territory. It was the third week of September, 2001, and (thanks to the kindness of Alan and Mary Young of Midnight Sun Outfitters) this was actually my second hunt for grizzly in that same calendar year. The spring hunt had brought no success, and we were all most hopeful that the fall hunt would bring a change of luck.

This short story about mountain caribou is a true tale that took place within a larger story, which the reader will find in Chapter 27 of BAREBOW!, under the title “The Moose-died-in-the-wrong-place Debacle.” Although the primary focus of the hunt was on grizzly bear, without question I had taken the Young’s advice and purchased both a moose tag and a caribou tag.

After taking a quick look through my binos at the pair of caribou racks in silhouette, I pointed and said, “Gerald, look up there in that high saddle, and tell me what you think about maybe going after those bulls.” The two animals were still standing there, stock-still, framed perfectly by a sapphire-blue backdrop.

After studying them through his optics for about 20 seconds, Gerald delivered his opinion: “Dennis, I’m not sure I’ve ever seen a bigger frame to a caribou rack. Since the grizzly we found yesterday morning didn’t show up today at the moose-kill site, we might as well spend our time between now and sundown trying to get a shot at a trophy like that. They’re likely to hang around up there all day, unless some wolves get after them. But getting over and up there won’t be easy. It’s about 11 o’clock now; if you feel like tackling that mountain, then let’s do it!”

“Well, I’m game,” I replied enthusiastically, “but are you feeling up to it? You’re the one who had a fever all night and were really feeling punk this morning. Do you feel up to that kind of a climb? We sure don’t have to do this today!”

Gerald smiled and nodded, saying, “I guess it’ll either kill me or the bugs—one of us. Let’s go!”

He still looked rather green around the gills, and I really felt for him, but—if he was willing to give it his best shot—I sure wasn’t going to try to talk him out of it. We headed back to the boat, and 15 minutes later, having traveled a half-mile downstream below the outlet of the lake, we tied our craft to a clump of willows and began cross-countrying toward the base of the mountain.

Once we started hiking, the high saddle was no longer visible to us, so from that point forward faith and hope became the twin engines of our resolve. It was a long, tough climb. Out-of-sight does not mean out-of-mind, however, and—as I struggled for the final two hours against what I call the “endless up”—the image of those spectacular antlers of that one huge bull was dancing constantly in my head. At about 2:30 p.m., we crested the ridge, at long last, and started following it toward the saddle. Would the two bulls still be there? Would there be others, perhaps, as well, which we hadn’t been able to see from down at the lake?

As we peeked over the last rise that was blocking our view of the saddle, the “good news” and the “bad news” hit us in the same instant. Both bulls were still there—having seen no reason to change their location in over three hours, but the “bad news” breeze that suddenly accosted the backs of our necks was about to give them one. Gerald and I looked at each other with frowns on our faces, realizing there was no help for the problem. We were now far above the tree line, and the topography around us could offer no help—if, indeed, they were about to catch our scent. Even though we were still a good 300 yards away, they were bound to smell us sooner or later—unless the wind in the saddle was doing something quite different from what we were experiencing. Unfortunately, it didn’t take long.

I was lying prone on the ground filming the two bulls with my camcorder, when I suddenly saw the big one lift his head and stare in our direction. His younger compadre followed suit. They had been sparring in the typical pre-rut rituals with heads lowered, horns engaged—pushing and shoving back and forth, with a distinct lack of any hormonal urgency. Of course, the rut was yet a couple of weeks off. Had it already been underway, these two bulls wouldn’t have even been keeping company, as there could’ve been no contest here for dominance or breeding rights.

They soon began milling around, seemingly uncertain as to whether they really should be concerned about that strange scent in the air. I had the impression, as I watched them through my camera’s viewfinder, that they had never encountered human odors before. So very light is the human hunting pressure in the Yukon that this was entirely possible. The caribou have to deal with wolves and bears all the time, but I really doubted these animals had ever smelled, or looked upon, a human predator before. It remained to be seen just how deep their level of curiosity might run.

Their milling about only lasted a minute or two before they began trotting away from us around a side-hill and out-of-sight over a hummock that served as their entrance to a very large alpine basin. As soon as they had disappeared, Gerald and I started running after them. When we peered over the top of the hummock that bore their fresh tracks, we spotted them again a quarter-mile or so ahead of us, with their heads down, feeding, as if they had not a care in the world.

But I think it was pretense—at least, in part. Every little while, one or the other would lift his head and look back up the hill in our direction. They were—as I was soon to learn—extremely curious to get a good look at what kind of critters could possibly have emitted such a strange odor.

They had put themselves in a position where nothing other than an earthworm could have approached them sight-unseen. My guide and I discussed our very limited options, and it was quickly decided that he would stay behind, while I would expose my self completely to their view and walk obliquely in their direction. By discarding all forms of “sneaky” behavior, I was hoping their native curiosity might yet give me a chance—if I could manage to mask my true intentions as a predator bent on premeditated malice. Upon taking leave of Gerald, however, I made a mistake I was soon to regret. I left my daypack with him, and the two cameras that were inside it.

With bow in hand, but no arrow yet on the string, I diagonaled my way down the slope more or less toward my fascinated quarry. No more than two steps had I taken before all four eyeballs were riveted upon me. After I had cut the distance between us to around 200 yards, the bulls began to move across in front of me and then up the hill to my right. They disappeared temporarily into a steep, little draw which seemed to top out on a bench well above me. As best I could, I angled uphill at a trot toward the top of that draw, knowing I could never get there in time.

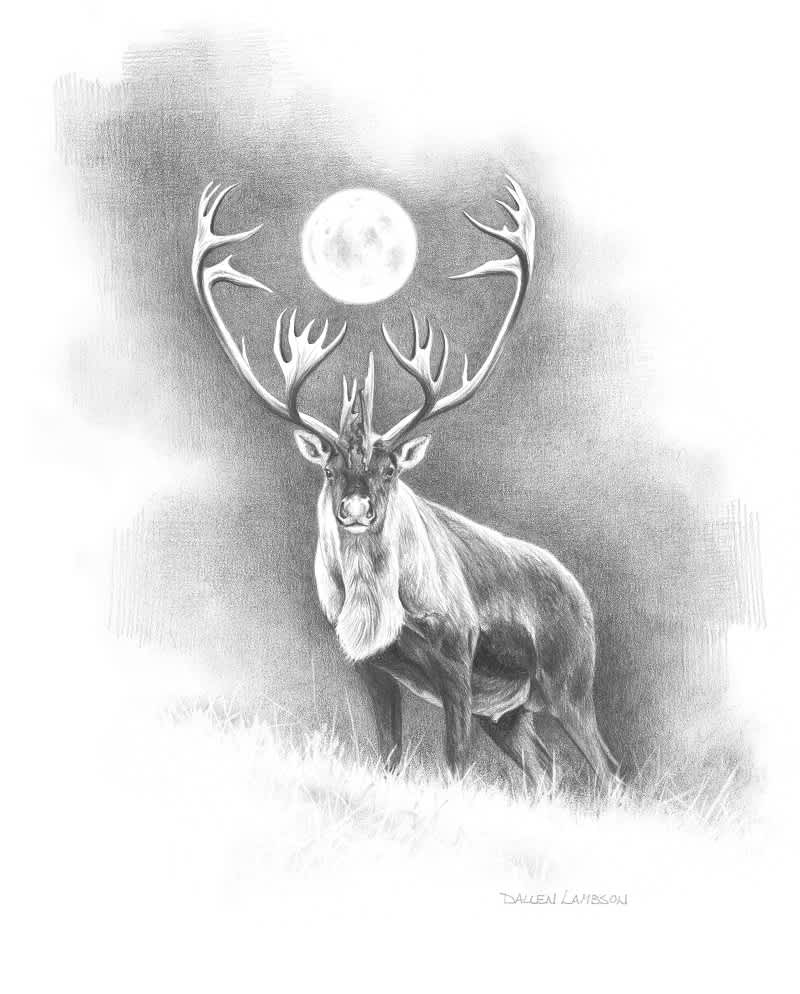

Then, all of a sudden, they were there! Silhouetted once more against the deep cerulean sky, standing stock-still and looking down upon me from the left-hand terminus of the bench. They were now less than 100 yards distant, and the sight that greeted me took my breath away—even before I could raise my binoculars to my eyes. The larger bull was a true monster, the bull of my dreams (and then some), possessing a set of antlers that I know would have scored well over 400 Boone and Crockett points. But what absolutely stupefied me was that—from my vantage point where I stood —the rack of the big fellow seemed to be holding a giant, round, Christmas-tree ornament between the out-stretched fingers of the top of each main beam! It looked like the perfect orb of a full moon—which, in fact, is exactly what it was!

It was one of those scarce, full moons you can occasionally see during the day, when the sun, moon, and earth are all in the right position. That mid-afternoon, the sun was at my back, and—as the magnificent bull and I stood there looking at each other for more than a minute, both motionless—I swear that a jeweler’s precision could not have set that moonstone in a more perfectly-centered position than where happenstance had placed it in the crown of that caribou rack! Through the magnification of my binos, the lunar physiognomy stood out in amazing detail, and that picture of a “moon over my antlers” will stand out in my memory as one of the most incredibly beautiful sights I have ever witnessed. The eight-power, magnified image was absolutely surreal!

Oh, what sum of money I would not have given for either one of my cameras right then!

It was the big bull, of course, that broke the magic spell by beginning to jog along the bench above me, with the smaller one in tow. They soon were out of sight for me, but I knew Gerald would be able to see them from his location. In order to keep them in view, he had had to retrace his steps nearly back to the saddle where we originally found them, and when I finally rejoined him the two caribou were several hundred feet in elevation above us, not far below the craggy summit of Castle Peak itself. It seemed they had thought they could circle the summit in that direction, but the terrain had become even too precipitous for them.

Gerald was the first to realize they were sort of trapped up there and would be forced eventually to retrace their steps across the top of us. At his insistent urging, I began “running” as fast as I could, straight up the steep slope that rose above us. At that elevation, on such a slope, “running” is a relative term, and within a minute or less I was breathing about as hard as a man can breathe. The incline to the slope was worsening steadily, and before long I was clawing at the hill in front of me with one hand, trying to maintain at least a modicum of upward progress. Suddenly, I heard Gerald shouting from way below. He was telling me to climb faster because the bulls were now coming back toward me and were about to pass above me again.

As I saw their forms appearing, I fumbled an arrow onto the string and tried to set my feet so I could draw. The problem was, the slope was so steep now, that the lower limb of my bow—as I tried a practice draw—was bumping into the earth in front of me! About this time, the big lead-bull spotted me and paused for just a moment. He was about 70 yards above me and a bit off to my right. As I came into my anchor position at full draw, I could see he was about to go into motion again, so I aimed three feet in front of him and sent the shaft on its way with a prayer.

My perception of what I thought I saw evidently didn’t square with reality. It looked to me, for all the world, as if he stepped right into the path of my arrow, but I guess wishful thinking was overpowering my eyesight. I heard no sound of impact, saw no sign of blood appearing on his white mane, and nothing about the slightly-accelerated gait of my departing bull-of-twenty-lifetimes seemed at all abnormal. The inescapable conclusion was that I had missed him clean.

On the hike back down to Gerald, and then on to Elliot Lake that evening, I mused deeply over the remarkable afternoon’s events. The philosophical thought occurred to me that—just as many men never find the woman of their dreams, let alone have the chance to marry her—so, too, many hunters never find the bull of their dreams, let alone have the opportunity to harvest it. I was truly lucky on all counts. Not only had I just seen the bull of my dreams and had a chance to take him, but soon I would be headed home to share the wonderful tale with the “lovely Karen,” who has constantly been the woman of my dreams, ever since I was fortunate enough to marry her in August of 1989.

Editor’s note: This article is the forty-eighth of the BAREBOW! Chronicles, a series of shortened stories from accomplished hunter and author Dennis Dunn’s award-winning book, BAREBOW! An Archer’s Fair-Chase Taking of North America’s Big-Game 29. Dunn was the first to harvest each of the 29 traditionally recognized native North American big game species barebow: using only “a bow, a string, an arrow—no trigger, no peep sights, no pins—just fingers, guts, and instinct.” Each of the narratives will cover the (not always successful, but certainly educational and entertaining) pursuit of one of the 29 animals. One new adventure will be published every two weeks—join us on the hunt! You can learn more about the work, and the various editions of BAREBOW! available, by clicking here: http://www.barebows.com/. You can also follow BAREBOW! on Facebook here.

Top illustration by Dallen Lambson