Bagging Birds with a Bow

James Swan 09.06.13

“And what do you think that you are doing with that?” my friend asked as I walked out the door of the lodge carrying a recurve bow with a quiver of arrows strapped on my back.

“I’m going hunting,” I replied, with as much of a straight face as I could muster.

“This is not a rabbit hunting club,” he replied.

I responded, “Yah, and game hens are $7.49 a pound and quail are three bucks each at Whole Foods. This is about sport more than meat.”

I’ve heard that a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush. And surely if you want that bird in the bush to be in your hand, your chances are certainly better if you are planning to shoot the bird with a 12 gauge and #8s.

If friends are coming over for dinner, I’ll shoulder my shotgun and shoot birds with it. But if I’m going out for a good time, I like a challenge. That’s why I hunt game birds on the wing with a bow and arrow.

Accurate wingshooting of flying birds with a bow requires being ready to draw, shoot, and release quickly and with centered concentration. A compound bow might work, but you never quite know for sure when the bird will flush and trying to walk with a drawn compound bow is beyond my comfort level.

Personally, I use a traditional recurve bow that Don Adams made for me 35 years ago: it sports a 55-pound draw and a custom grip that fits my hand like a handshake. The recurve draw allows me to start aiming the second the bird takes off. And it is a smooth draw that allows me to keep my eyes on the target. My shot is a quick, smooth draw, track, and shot—all instinctive—and is often over with in as much time as it would take me to me to get a compound drawn and anchored.

My arrows are flu-flu-fletched, which I make myself. Whenever possible I like to use feathers from turkeys or geese that I have bagged.

The shaft of the arrow can be either wood or aluminum. I prefer wood, but the basket point that you need for chukar and quail has a screw in attachment, so that requires an aluminum or fiberglass arrow.

On quail, chukar, and pheasant, I use a Martin screw-in 295-grain bird point. The goal is to have the blunt point in the middle of the basket point hit the bird in the head or body. The shock brings them down like a rock. However, this is a flying bird, the target size of which is about the same as a baseball. The four three-inch circular wires surrounding the blunt point can also bring down a bird if they hit the head, or catch and break a wing.

A hard rubber or metal blunt point also works well. These are best when shooting at a bird that is on the ground or in a tree, or a rabbit for that matter. Basket points don’t work well on the ground as a few blades of grass stop them cold. There are now a number of different points that expand the lethality of your shot.

In the case of pheasants, I might also use a hard rubber broadhead screw-in point, as the bigger a bird is, the harder it is to bring them down. The rubber points are obviously not as sharp as a real broadhead, but you will not get cut with them if you stumble when walking up to the dog on point, like you could with a broadhead. I have never shot a duck or goose on the wing with a bow, but I’d like to give that a try.

By far the best way to wingshoot birds with a bow is with a pointing dog. You can get prepared, walk up slowly, flush the birds, and the shots are close, only 10 to 15 yards. Beyond 20 yards, forget it, as the flu-flu feathers break the speed of the arrow so much that you lose the lethality of the shot any farther out.

Yah, I will sometimes shoot a bird on the ground, or sitting in a tree. A quail, grouse, or chukar is a pretty tiny target, especially if you try to hit it in the head—which is about the size of a big marble. Sometimes spruce grouse just won’t fly. Ptarmigan like to scurry in rocks, rather than fly, unless they have been heavily hunted. Dusky or blue grouse often prefer to sneak along in ferns or blackberries rather than take flight.

Where you do you aim? Always, when a bird is in the air, I aim for the head, or better still, the beak. The bird is going to be moving headfirst, so that guarantees a lead. A blunt point kills by shock. Hit them in the head and it’s a clean, quick kill. Otherwise, a heart-lung kill zone shot, as with big game, always brings them down immediately due to shock. When you get much out of that zone, the bird might get a bruise, but that’s it.

I have three ways of practicing. The first, and most important, is visualization. Every day, regardless where I am, I practice archery by visualizing shooting arrows at various targets. I assume the shooting position, pick a spot, raise my bow arm out straight, and place my drawing hand at full draw anchor position on my cheek as I take in a breath. I point my index finger on my bow hand to simulate the point of an arrow, imagine a laser beam coming out of that finger and striking the point, hold my breath and then release when it feels right. Then exhale.

So long as you keep yourself physically fit with push-ups, weights, and such so that the actual draw weight of the bow is not too much for you when you do draw an actual arrow, practicing with mental imagery is the next best thing to actually shooting an arrow and it builds precision shooting instinctively. I learned the value of this practice method from champion clay pigeons shooters like Linda Joy and Kim Rhode, IPSC pistol champ Todd Garrett and, of course, the master wingshot archer of our times, Byron Ferguson.

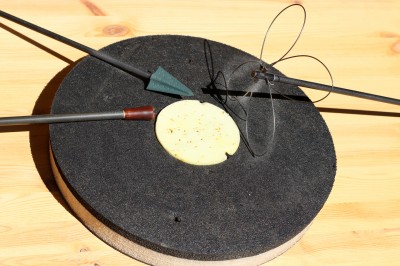

When I want to shoot arrows and I am by myself, I rig up a pendulum pole about three feet above the three bales of straw that are the backing for the target. I make a target from a piece of foam about the size of a softball, or a similarly-sized small burlap bag filled with sand. I tie the target to a five-foot-long piece of cord, and start the pendulum swinging. Then I step back to 10 to 15 yards and let fly. If you hit the target, it will keep the pendulum going for a long time in crazy ways, just like a bird.

If I have a partner, we take turns standing behind a tree or a building and tossing a dinner-plate sized foam target up into the air on the call of “bird.” The outer ring is black and the inner ring is three-inch diameter yellow circle, which is about the size of the kill zone on a chukar or a pheasant. It helps to have half a dozen such targets. Properly fletched flu-flus will travel about 40 to 45 yards, at most.

Do I get as many birds with a bow as with a shotgun? Well, no, but I’ve bagged quail, chukar, and pheasant with a bow. When you do it that way, somehow they taste better.

The nice thing, too, is that archery hunting extends your bird hunting seasons. For example, in California, the pheasant season runs November 14 through December 27 this year. But if you hunt pheasants with archery, the season stays open until January 12. Regular chukar and quail season starts September 12, but there is an additional archery-only season on both birds August 15 to September 4. And of course for released birds, you can hunt them with a bow as long as anyone else.

Perhaps best of all, when you bag a bird on the wing with a bow, you feel connected to the long line of archers that have hunted with a bow for thousands of years. And when you bag a bird, you can almost hear them saying “Not bad for a guy who usually uses firesticks.”