Commemorating a Family Hunting Tradition in Southwestern Wisconsin

Patrick Durkin 12.03.13

Three flags at half-staff furled and flapped outside the farmhouse on the Richland County, Wisconsin hilltop, reminding our clan we’d never again chase deer with our hunting patriarch, chief storyteller, and proud family chauvinist.

So, we stopped our truck along the driveway, admired the bright flags above, and wondered what deer season would be like without Joseph “Terry” Durkin, who died November 1 at age 86. He and my Aunt Mona proudly shared this 200-acre farm with the family’s grateful hunters the past 30 years, and patiently heard the many deer stories that followed.

In truth, my uncle was far more passionate about family and heritage than deer hunting; as are most hunters, I assume. You sense this from the flags my cousins chose to keep his spirit near and their loyalties firm.

The large US flag atop the 35-foot flagpole reminds us of his five years in the Navy and nearly 30 years with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Below, the red Bucky Badger flag honors his play on Wisconsin’s 1953 Rose Bowl team, and the green flag flaunting a yellow harp needs but three words to say it all: “Erin go bragh,” or “Ireland forever” in Gaelic.

Still, Uncle Terry’s eyes twinkled with appreciation whenever admiring deer hauled home by sons, grandson, nephews, or grand-niece. Even as failing health shortened his time in the woods and lengthened his time indoors, he dropped his newspaper, grabbed his camera, and went outside to praise every deer we brought in.

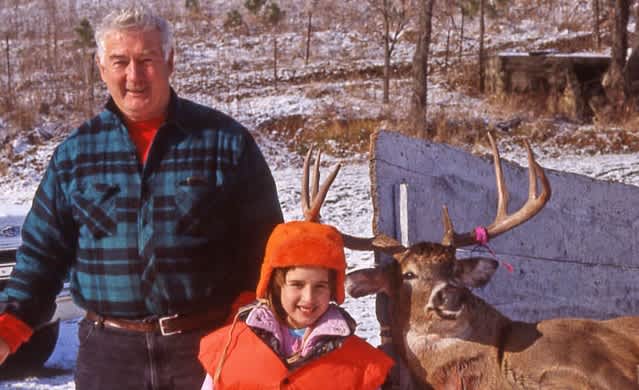

But make no mistake: Uncle Terry was a good shot and serious deer hunter. That was never more obvious than the second day of 1991’s deer season. That’s when my daughter Leah—then six—joined our group.

Leah and I sat through a cold, windy opener, ducking our heads and turtling our necks as soggy snowflakes soaked our hats and splattered our cheeks. I shot two does that Saturday with Leah beside me, her persistence earning my aunt and uncle’s praise.

In turn, we volunteered our Sunday morning to walk the farm’s western and northern fence lines in hopes of pushing deer past Uncle Terry 500 yards to the east. As we crested the farm’s farthest hill about 9 a.m. that day, we heard him shoot. We quickened our pace, but kept following the boomerang-shaped ridgeline to the tractor trail, just as he had instructed.

Then we hurried to his treestand, eager to see what he had shot. We assumed success. He never shot wildly.

Sure enough. We found a fresh gut pile 30 yards from his stand, but a long, pink-flecked furrow in the snow showed he was already dragging the deer. “What’s his hurry?” I wondered.

We didn’t catch up until reaching the rural highway a half-mile below. As we neared my uncle, we saw an antler reaching nearly to his knee and a violet deer tag tied to its thick base. We cheered, shook hands and listened as Uncle Terry told his story to us and his sons.

He said a small herd had burst from the brush below Leah and me soon after we disappeared on the far hill. They ran past without offering a good shot, and disappeared into the draw south of him. Minutes later, a doe sneaked nervously from the draw and headed his way. Large antlers soon jutted above the skyline behind her, and a thick-necked buck with a steer-sized head followed.

My uncle said he muttered “Mama Mia!” (maybe he did, but I never heard him use that expression except that once). He then waited for the buck to walk so near he could have shot it with a bow, and dropped it with a neck shot to ensure it didn’t suffer.

Uncle Terry was just that way with animals. Meanwhile, he worried whether it had already passed along its genes, and lamented that it would never again walk his fields and woodlots.

Then he paused, smiled and said: “I’m late for Mass. Mona’s waiting. You guys load him up. Leah and I will register him later.”

And that’s what we did. That night, as I drove Leah home, she said Uncle Terry couldn’t have killed the buck without her. I asked why she thought that.

“That’s what he said,” she replied. “That’s what he told everyone at the gas station.”

I don’t know if that event locked in Leah as a deer hunter, but we’ll try tapping into Uncle Terry’s unselfish spirit whenever hunting in the years ahead.

And while we’re at it, we’ll recall a Gaelic phrase from his eulogy: “Ar dheis De go raibh a anam.” Or, “May his soul be on God’s right side.”