Up a Creek with No Paddle? Never Again!

Patrick Durkin 08.18.15

A young couple who are friends with my youngest daughter often hike, fish, and camp in remote areas of northeastern Minnesota’s Superior National Forest and Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness.

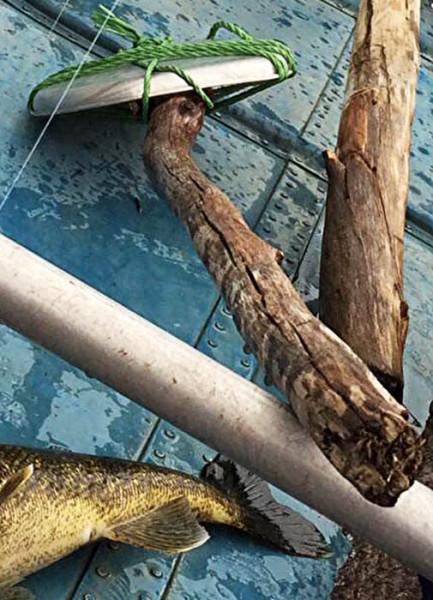

After one of their trips this summer, they posted photos of their chilly weekend, including a picture of two walleyes in the bottom of a canoe. I recognized Jenny You, 26, in the canoe’s bow, and assumed her fiancé, Nick Anderson, 31, was the cameraman in the stern. Also in the canoe was a long piece of bark and a thick stick with a pan lashed to one end.

Hmm. Suddenly, I was more interested in the wood than the walleyes, and called to hear their story. They said they had hiked about a mile into the Superior National Forest after going as far as they could risk in their car. After following a game trail toward a lake on their maps, they pushed through brush trying to reach the shoreline. They hoped the shoreline would be the best way to reach the lake’s water-accessible campsite on the far side.

Easier said than done, of course. They soon found themselves busting through nearly impenetrable brush. Their luck changed when they stumbled onto an old aluminum canoe someone had stashed behind some boulders, making it invisible from the lake.

Rather than persist in their tortured stumble to the campsite, they agreed the canoe was their salvation. After all, it likely hadn’t been used in years, and they’d return it when finished.

There was only one problem: no paddles. Anderson and You searched the area, thinking the owner might have stashed paddles nearby, but found nothing.

In effect, they were like the characters in Adventures of a Young Man, a 1939 book by John Dos Passos, who wrote: “It was dark; they had a hard time finding their way through the woods to the place where they’d left their canoe. The mosquitoes ate the hides off them. ‘Well, we’re up (blank) creek without any paddle.”

Anderson, a family physician in Shoreview, Minnesota; and You, a TV reporter in Coon Rapids, Minnesota, agreed they’d still rather continue their journey to camp over water than through the brush. They aren’t moose, after all. Besides, Anderson rowed on the University of Minnesota’s crew during college, so they felt confident they could make something work.

Before long they found a wide piece of rotting poplar, its bark still attached, and thought it might suffice as a paddle. Next, they found a long stick about as thick as a 2-by-2, and declared it good enough. After dragging the canoe to the lakeshore, You climbed into the bow with the thick stick, and Anderson settled in the stern with the punky piece of poplar.

The going was slow, and pieces of poplar broke off and floated away as they crossed the lake, which is about a mile long and half-mile wide. But the old canoe didn’t leak, and eventually they reached land and set up camp. Next they broke out their fishing gear and the leeches Anderson packed, and decided to go back out to try for walleyes.

They caught some, but the more Anderson paddled with his poplar, the more it fell apart. After surveying their gear, Anderson lashed an aluminum plate to You’s stick with some rope, crisscrossing it several times before securing it tightly with a knot. It failed once, but after Anderson tied the plate back into place, it held up the rest of the weekend.

“Nick has some good Boy Scout skills,” You said. “It worked pretty well. It was surprisingly effective.”

When eating some walleyes that night in camp, they had to share their remaining plate. And when heading home after fishing again the next day, they paddled the canoe back to its hiding place and left it as they had found it.

Their story reminded me of a longtime friend, Joe Shead of Superior, who has a knack for turning ordinary fishing and hunting trips into adventures. He, too, knows of a small Northwoods walleye lake that’s about a mile walk from the nearest road. He’s fished it often on opening day with a canoe that’s been stashed there for decades. “Usually there’s a paddle under it,” Shead wrote recently. “One year there wasn’t.”

So, he inspected a rotting fiberglass boat nearby, broke off a piece of its dilapidated hull, and used that as a makeshift paddle. “Of course, it had to be windy and snowing like crazy that day,” Shead wrote. “I can tell you this: a chunk of fiberglass isn’t nearly as effective at propelling a canoe as a paddle.”

Other serious paddlers I contacted said You and Anderson did exactly what more experienced canoeists have done in emergencies: fashioned a paddle from a stick and plate. However, some plan for emergencies by packing just a paddle blade, and cutting a pole and taping or tying them together.

Darren Bush, owner of Rutabaga Paddlesports in Madison, said other options for campers and backpackers are four-piece breakdown kayak paddles, and adjustable-length paddles that can be shortened to 48 inches. He said the recent advent of paddleboards inspired the original adjustable-length paddles, and the idea expanded into canoe paddles, especially for parents who don’t want to keep buying new paddles for growing kids.

Bush also said that although flat, wide blades make the most efficient paddles, just about anything pulled through water provides some propulsion. Stu Osthoff, editor of the Boundary Waters Journal magazine in Ely, Minnesota, agreed, writing:

“The beavertail paddles used by Indians and voyageurs were actually very narrow, probably because there was no reliable glue/lamination systems back then.”

Still, Bush and Osthoff recommend using quality paddles to prevent emergencies, and carrying a spare whenever possible—which You and Anderson have done on subsequent trips to their secret lake and stashed canoe.

“For the record, I’ve paddled thousands of miles with the Bending Branches Expedition Plus paddles, and never broken one,” Osthoff wrote. “I give this paddle to all my clients. If you buy a good, tough paddle and don’t do stupid things with it, you should never need a spare or be in the position to have to cobble one together.”

And that’s how you avoid getting stuck up Ship Creek without a paddle.

That is its name, right?