Video: A Behind-the-Scenes Look at Oregon’s Wild Steelhead Broodstock Program

Randall Bonner 03.02.18

With all the obstacles and adversity that our steelhead populations face, hatcheries are a necessity in order to have sustainable populations that allow for harvest. To ensure the best genetics possible for hatchery production, the capture of wild broodstock is also a necessity.

Capturing wild broodstock is done by two different means. Ideally, the wild broodstock are line-caught and collected by anglers. Supplemental wild broodstock are collected when they are caught in hatchery traps and fish weirs.

The hypothesis being tested at the Oregon Hatchery Research Center (OHRC) in Alsea, Oregon, is that using line-caught wild broodstock develop the genetic disposition for their offspring to be line caught as well. Wild broodstock are caught by anglers and placed in tubes for pick up by Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife hatchery personnel. The tubes are placed with the fish facing upstream so that a constant supply of freshwater flows through. The tubes themselves are somewhat constricting to the movement of the fish, but this also prevents them from injuring themselves. The enclosure also reduces stress on the fish by acting as a visual buffer for environmental disturbances. “The fact they can’t see anglers or potential predators makes them feel safe and keeps them calm inside the enclosure,” said hatchery worker Eric Hammonds.

After fish arrive at the hatchery, they are placed into a small container with an anesthetic that makes the fish easier to handle without causing physical damage. Once the anesthetic has taken effect, the fish are given an antibiotic injection to prevent them from picking up diseases or fungus growths while being held at the facility. This precaution is taken because the process of handling the fish removes some of their protective slime layer that defends them from these infections.

The fish are tagged and placed into circular tanks and held until they are “ripe” to be spawned with a paired mate at the hatchery, and then released back into the river. The program typically shoots for a goal of 40 pairs of wild broodstock fish, but rarely reaches that goal due to the combination of low returns and lack of participation in the program.

Traditional hatchery broodstock tend to have muddy genetics. Because they are spawned from the same pool, they lack the genetic diversity of a first-generation wild broodstock fish born from wild parents. The theory behind the OHRC “Biter Study” is that decades of spawning hatchery fish that return to the trap has evolved that stock to become less likely to be angler caught, because most hatchery fish caught by anglers are harvested, rather than spawned.

Traditional hatchery broodstock and first-generation wild broodstock (or “F1” fish) are marked with an adipose fin clip, and separated by maxillary clips that differentiate returning hatchery adults as traditional broodstock or F1. Unlike the collected wild broodstock fish that are returned to the river after being spawned, the returning traditional hatchery broodstock bucks are typically killed when they appear in the trap, while the females are stripped of eggs and returned to the river to swim back to the salt and return again. This practice ensures that the two groups of fish are less likely to spawn with each other in the gravel.

Opponents of the program argue that wild steelhead populations can’t sustain being farmed to create hatchery fish for harvest. It is also undeniable that there is room for human error in this process. While the success rate for wild broodstock collection is extremely high (in the upper 90 percent range) there are accidents that happen. Adult fish left in collection tubes are susceptible to theft by poachers. Reporting the collection of a wild broodstock fish to hatchery personnel as quickly as possible is the best way to prevent these kinds of incidents.

Some wild broodstock collection programs employ the use of livewells complete with battery-operated water circulation to aerate the water and keep oxygen levels high during transport. However, battery failures, or contamination of the livewell, can also create problems and cause casualties. Even still, such incidents are extremely rare and represent less than 1 percent of the wild broodstock adults collected.

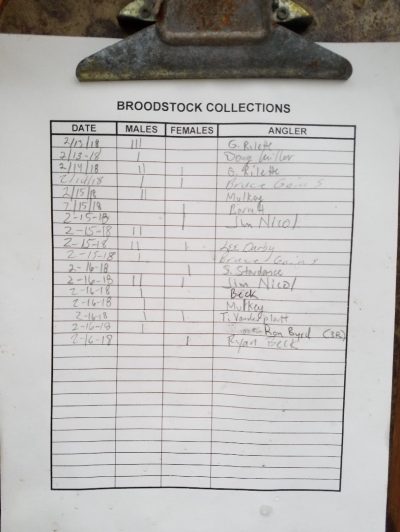

Wild broodstock programs are typically funded and operated by volunteer organizations. The Alsea Sportsman’s Association provides the collection tubes for the Alsea Hatchery and the OHRC biter study project. Tillamook Anglers and Nestucca Anglers provide livewells for the Nestucca River and surrounding Tillamook rivers that participate in the Wild Broodstock programs. While personnel from the Alsea hatchery handle collection during business hours, the Cedar Creek hatchery on Three Rivers (a tributary of the Nestucca where hatchery operations are conducted) has a self-service option for wild broodstock that are collected and brought to the hatchery after hours. There, they are placed into a raceway and marked by quantity and sex on a self-service report form.

The Nestucca wild broodstock collection program quota is 65 pairs. Fish that are placed into the raceway are given Parasite S (Formulin) 5 days a week administered by a flow-thru treatment to keep fungal growth at bay. The raceway is fed through an up-welling system, rather than fed from one end to the other. This prevents fish from following their natural jumping instincts, and reduces physical stress. When it’s time for pairs to be spawned, the fish in the raceway are collected using a “crowder,” which essentially functions like a seine net that allows personnel to net the individual fish for spawning, and pass fish that aren’t ripe back over the crowder and into the raceway.

The quotas for wild broodstock collection are determined by the number of required adults to produce the required amount of eggs to produce the required amount of smolts for release within a margin of loss during the process. These quotas of adults collected for the program are determined to be 1-2 percent of the wild population, mostly by historical data from redd surveys.

While the survival and success rates are high at the Cedar Creek Hatchery program with less than 1 percent of wild broodstock adults lost (and most of those by angler error), the Alsea Hatchery program has endured some challenges in recent years through equipment failures. The chillers that keep the water at necessary temperatures to prevent loss of eggs failed 2 consecutive years before being upgraded and replaced with new wiring and equipment. New collection cages for wild broodstock collection were installed at boat ramps on the nearby Siletz River, where the Alsea also handles wild broodstock collection and spawning at their facilities. Several adults were lost at the hatchery due to complications with the sharp, abrasive edges on the metal inside the cages at collection sites, which caused severe physical damage and unnecessary stress to the fish that were collected. The cages have since been sprayed with a material used for truck bed-liner to prevent future complications and casualties.

Unlike the Cedar Creek facility, the Alsea hatchery uses a circular PVC tank system that is intended to cause less harm by using smooth surfaces and removing the concrete corners that are typically standard with the construction of rectangular raceways. In recent years, additional circular tanks have been added to the facility in an effort to reduce crowding of the fish.

As of a week prior to this story being written, the number of wild broodstock fish being collected by anglers at the Alsea Hatchery pales in comparison to the numbers at Cedar Creek’s facility. At a recent Alsea Sportsman’s Association meeting in Waldport, a hot topic of discussion was the lack of angler participation in wild broodstock collection due to mistrust in the handling of the program by the Alsea Hatchery during recent years. Even with upgrades and equipment repair, the wild broodstock programs that operate at the Alsea Hatchery are still trying to repair their public relations. Hopefully learning from some past mistakes will help the program continue to improve, and regain the trust and participation from local anglers and guides. Meanwhile, the wild broodstock program on the Alsea River is trying to portray a positive image in negative time.