Court Rules in Favor of Hunters in Wyoming Corner-Crossing Case

Keith Lusher 03.26.25

A federal appeals court has sided with hunters in a case that could change how people access millions of acres of public land in the western United States.

The 10th Circuit Court of Appeals unanimously ruled on March 18 that four Missouri hunters did not trespass when they “corner crossed” between sections of public land during elk hunting trips in Wyoming.

What is Corner Crossing?

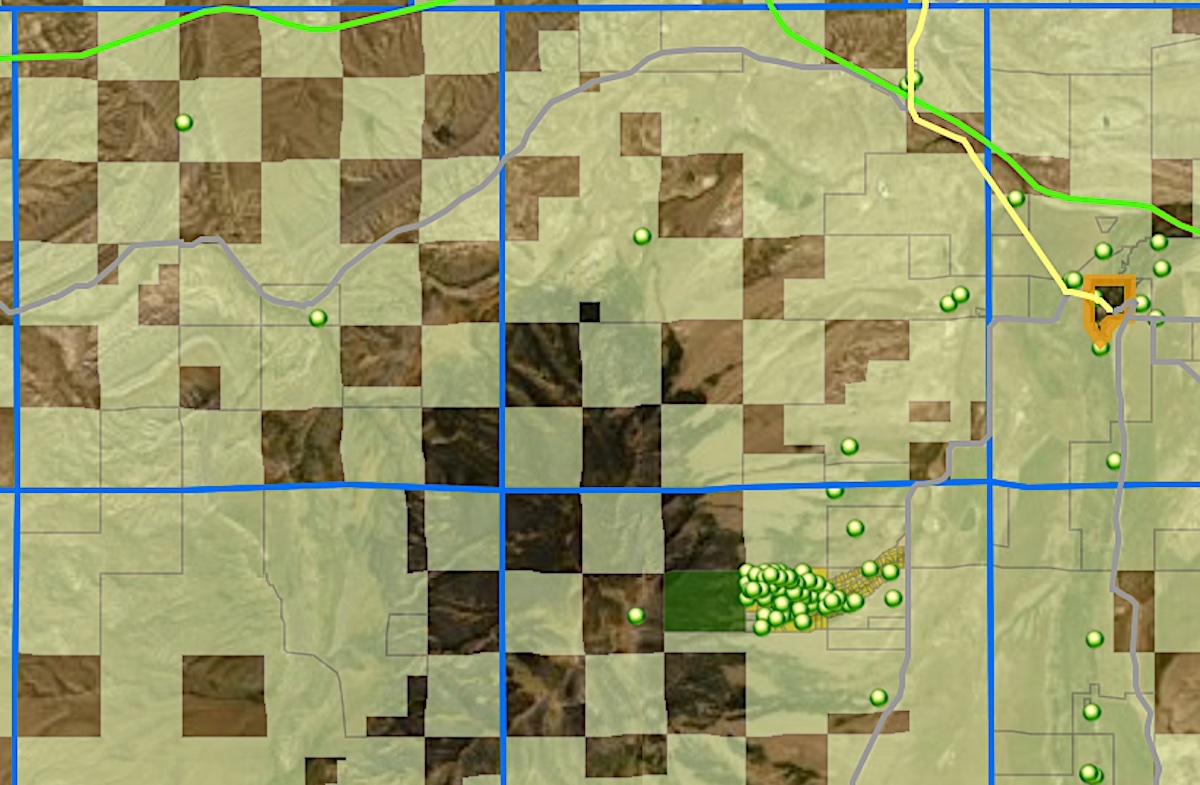

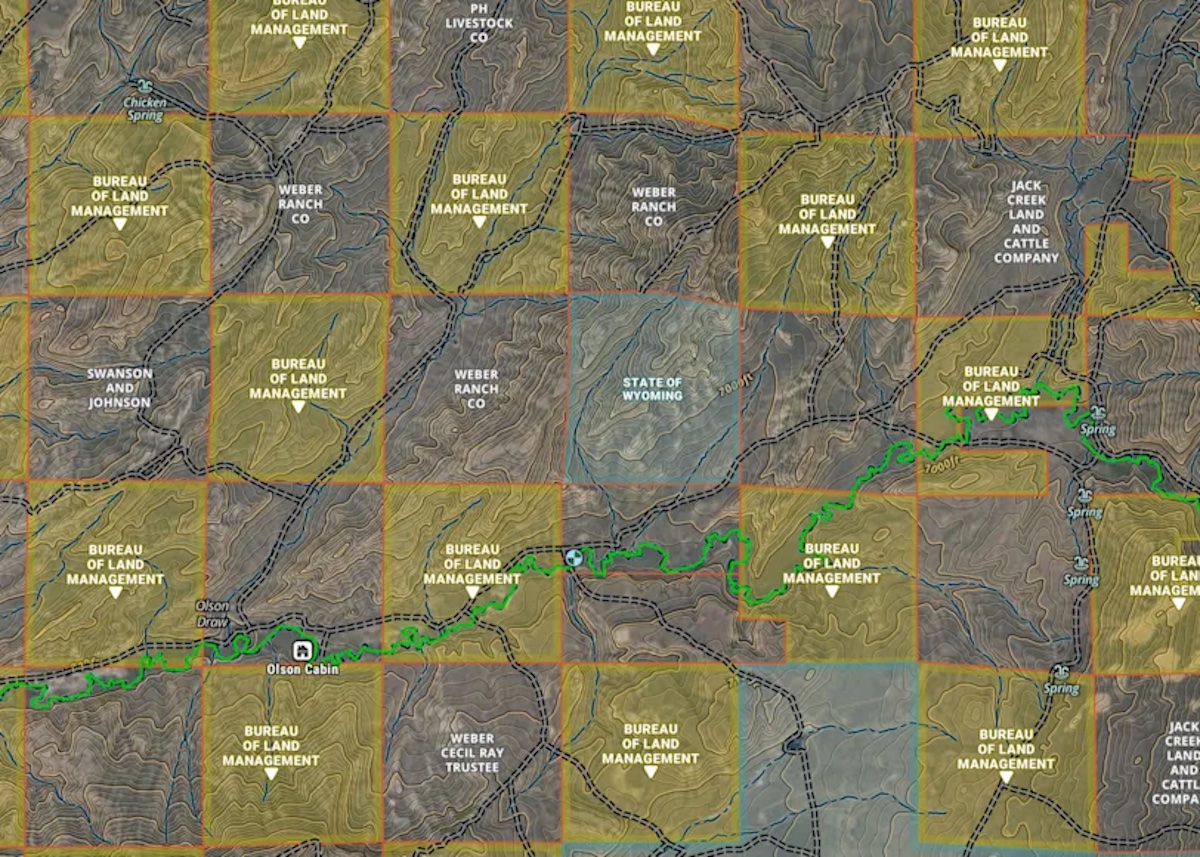

“Corner crossing” happens when someone steps from one piece of public land to another at a point where four land parcels meet at their corners – two public and two private – without setting foot on private land. This checkerboard pattern of land ownership is common across the West, created in the 1800s when railroads were granted alternating square-mile parcels.

The Case That Started It All

Brad Cape, Zachary Smith, Phillip Yeomans, and John Slowensky went elk hunting on Bureau of Land Management (BLM) land near Elk Mountain, Wyoming in 2020 and 2021. They built a ladder to help them step across corner points without touching private property.

“Nobody in my part of the world knew that corner crossing was an issue,” Cape told reporters. “That struck everybody’s fancy — just a curiosity of, ‘how could this even be a thing?'”

Their actions upset Fred Eshelman, a pharmaceutical executive who owns the 50-square-mile Elk Mountain Ranch surrounding these public land sections. After failing to win criminal trespassing charges against the hunters, Eshelman filed a civil lawsuit through his company, Iron Bar Holdings.

Eshelman claimed his ranch would lose $7-9 million in value if he couldn’t control access to roughly 11,000 acres of public land nestled within his private holdings.

What the Court Decided

The three-judge panel ruled clearly: “The Hunters could corner-cross as long as they did not physically touch Iron Bar’s land.”

Their 49-page decision relied heavily on a 140-year-old law called the Unlawful Inclosures Act of 1885. This law was created to stop wealthy landowners from blocking access to public lands. It forbids “obstructing transit over public lands by force, threats, intimidation, or by any fencing.”

The judges determined that federal law protecting public land access overrules Wyoming’s trespass laws in this situation. As they wrote, a different ruling “would place the public domain of the United States completely at the mercy of state legislation.”

Why This Matters

This ruling could open up millions of acres of public land that were previously difficult to access. According to mapping company onX Maps, about 8.3 million acres of public land across the West are “corner-locked,” meaning corner crossing is the only way to reach them without crossing private property. Montana alone has nearly 900,000 acres in this situation.

The decision applies to six states in the 10th Circuit: Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, Oklahoma, and Kansas.

Ryan Semerad, the lawyer who represented the hunters, said the ruling confirms that corner crossing is legal “in a much more dramatic fashion than any previous rulings.” Wyoming Representative Karlee Provenza added that the decision means state legislatures cannot ban corner crossing under federal law.

Hunting and conservation groups celebrated the decision. The Montana Chapter of Backcountry Hunters and Anglers called it a “massive victory for public land access.”

“This ruling ensures public access to millions of acres of corner-locked public lands,” said Dagny Signorelli of Western Watersheds Project, calling it “a key win in the battle to keep public lands in public hands.”

Not everyone is happy with the outcome. The United Property Owners of Montana, which supported the ranch owner, argued that more corner crossing would lead to problems like poaching, littering, and fires on remote public lands. Chuck Denowh, their policy director, called the ruling “largely academic” and noted that “in most cases it is not evident where a property corner is.”

What Happens Next?

Eshelman and Iron Bar Holdings could appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, though legal experts say this might be difficult given the unanimous nature of the appeals court ruling.

As for Brad Cape, one of the hunters at the center of the case, he still has the ladder he built for accessing the public land. “Might use it again,” he said.

This case represents the latest chapter in the ongoing tension between private property rights and public land access in the American West, a conflict that began with the railroad land grants of the 19th century that created these checkerboard patterns in the first place.