Carrots and Sticks: Incentives for Ethical Hunters

James Swan 05.23.13

You’re out in the marsh in duck season. A flight of mallards comes over. You carefully pick out three big greenhead drakes. Three shots and seconds later, they are down in the pond. A triple. Wow!

You go out to pick them up. Suddenly one that’s wounded scoots off into thick cover. You shoot, but don’t connect and he’s gone. Just then, another flight of mallards appears, 20 yards high, coming right for you. The limit is seven. You could crouch down behind a clump of cattails and maybe bag two to three more. But, you decide that going after that wounded bird is more important. So, you pass on the new flight and plunge into that nasty thick cover, spending half an hour chasing the wounded bird. Finally, you recover it.

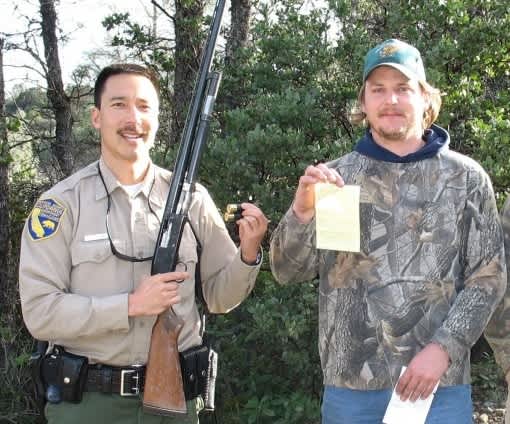

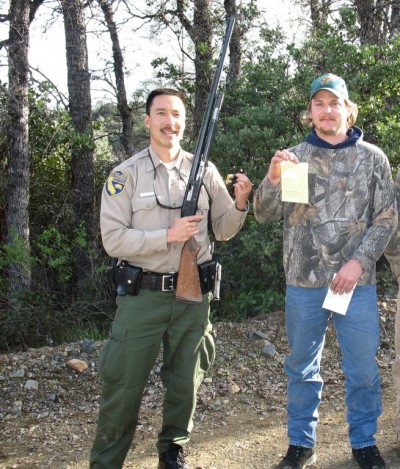

As you emerge from the marsh, a game warden is there, waiting. Your first thought is “What have I done wrong now?” He/she asks for your license. Now you’re really worried. They check it and begin writing out what looks like a citation. Finally, the warden hands it to you, smiles and says, “Good job.”

For several years in California, if a game warden gave a “Caught Doing Good” certificate to sportsmen for special acts of outstanding ethics they became eligible for a special season-end drawing for many valuable prizes. I recall a ride-along I did with California game warden Lieutenant John Laughlin when we found a couple who were picking up trash along the banks of the Sacramento River while waiting for a striper to bite. They had half a dozen big plastic bags filled when we met them. In the good old days these folks would have definitely been given a “Caught Doing Good” certificate. Funding dried up for the program. Too bad.

Hunters have become minority group. A recent public opinion poll by Responsive Management (pdf) found that while only about six percent of the general public hunts, 81 percent support ethical hunting. That’s heartening, but the same poll also found that 62 percent of the general public believes that a lot of hunters break hunting laws, are reckless, and drink to excess. The actual statistics of hunters who behave badly are actually less than one percent, but in a media-driven age, image is what counts, whether it’s accurate or not.

The image of the hunter perceived by the general public will play a key role in the future of hunting. Game wardens catching and punishing hunters who break laws is the “stick” approach. Ask any game warden how many of the bad guys they’re able to catch–most will admit that they can only catch a small fraction, even with various tip programs to report poachers and get a reward. The problem simply is that there are not enough game wardens anywhere–there’s about 7,100 for the entire United States.

There are several outdoor sports TV channels with a myriad of shows, but do non-hunting Americans watch them? The popular Duck Dynasty and American Hoggers series on mainstream TV networks help to acquaint non-hunters with hunters, but so long as we live in a system where ballots, court cases, media campaigns, new media, and administrative decisions can curtail hunting and there is a well-funded anti-hunting movement churning out propaganda, the modern hunter is an endangered species.

Psychological research has shown that carrots (incentives) are a more effective way to shape behavior than the stick (punishment). From numerous studies of crowd psychology, we also know that attitude in a group of people is contagious. Getting enough good ethical hunters out in the field practicing good behavior improves the collective attitude of all hunters, the image of hunting gets upgraded, and more people stay hunting. That’s one reason why programs like Caught Doing Good are so important.

The challenge is how to get more hunters presenting a positive role model image in the field. Another strategy to help upgrade the image of hunting is to set up a “Master Hunter” program to reward those hunters who take additional courses beyond the mandatory hunter education class to develop special skills and reinforce ethics and etiquette. A quick check online found such programs in Washington state, Delaware, and Oregon. There probably are many more.

Master Hunters might also perform special conservation service, which could include becoming a deputy warden, but without police powers. In law enforcement, “presence” is the best way to keep the peace. Such “warden assistants” could be invaluable to crowd control and overall behavioral ethics, especially in crowded situations like opening day in a state or federal duck marsh or opening day of deer season.

Hunter education instructors are also a positive image in the field. Perhaps Master Hunters and instructors, in exchange for helping build levees around a refuge, planting trees and shrubs on a state wildlife reserve, assisting a farmer build a barn or harvest a crop, teaching kids firearms safety, or helping manage crowds on a busy refuge opening day, could be rewarded with special access privileges to hunt on special state or private land, or maybe even a few extra days of hunting in a special season.

There are also special programs in an increasing number of states to certify archery hunters to hunt urban deer herds. They have to take special classes, pay a small fee to cover an insurance bond, pass a shooting proficiency test, and agree to harvest more does than bucks. In exchange, they get a freezer full of venison and do an awful lot of good community service, as well as saving communities hundreds of thousands of dollars. And people whose shrubbery is saved from hungry deer become ardent friends of the hunter.

Across the nation small game hunting is declining. A U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2006 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation found that from 2001 to 2006, small game hunting declined 12 percent and the number of duck and goose hunters declined by 22 percent, while the overall number of hunters rose between 2006 and 2011. I would guess that the decline in small game hunters (while deer hunter numbers are solid or increasing) is associated with the lack of access to free hunting grounds for the limited budget hunter who just wants to get out in the woods for some rest and relaxation. I also suspect that lack of cheap or free access is one reason why one-third of the people who take and pass a hunter education class do not go on to buy a license.

Let’s face it folks, if we can find ways to support ethical hunters who understand the value of doing good things and set a standard for good behavior in the field, the future of hunting looks a lot brighter. We need carrots more than sticks to keep the hunting heritage secure.