How to “Colony Raise” Rabbits for Meat

Jordan J. 02.28.24

If you’re interested in raising rabbits for meat, one option to consider is creating a sustainable “rabbit colony.” Colony raised rabbits are free to roam, dig, burrow, breed, and eat at will within a defined area, bounded by a fence that can keep the rabbits in an predators out. It’s a significantly different experience (for you, and the rabbits), from raising rabbits in cages, stacked on top of each other.

In this article, I’m going to share my experiences colony raising rabbits — why I decided to do it, how I set up my rabbit colony, and what my experience has been thus far. First:

Why Colony Raise Rabbits?

When planning any homesteading project, my goal is the pursuit of “permaculture,” defined, by Wikipedia, as “an approach to land management and settlement design that adopts arrangements observed in flourishing natural ecosystems.” Basically, if we’re going to grow crops and raise animals, why not do it as naturally as possible so that the operation flourishes organically and self-manages?

I’ve previously raised meat rabbits in cages, and it was not a pleasant experience. The cages got filthy and stayed filthy despite arduous weekly cleanings. The rabbits did not look happy. I had to frequently trim the rabbits claws, un-worn by regular burrowing. This time around, I wanted to try something different.

A rabbit colony offered the following attractive advantages:

- Natural Environment: A colony allows the rabbits to live their best natural life, burrowing, interacting with each other, expressing their own social dynamics, and having the “real life” rabbit experience.

- Reduced Workload: I never wanted to clean out rabbit cages again. Rabbits are naturally tidy animals (unlike chickens), and can be expected to “run an orderly operation” by themselves without a lot of human maintenance.

- Healthier Rabbits: Theoretically, the reduced stress and increased space in a colony environment contribute to healthier rabbits. This, in turn, could result in better reproduction rates and higher meat yields

Of course, many people have reservations and cite potential drawbacks, summarized below:

- Uncontrolled Breeding: Opponents of rabbit colonies feared rabbits would over-breed, hurting females, and causing genetic problems if sibling rabbits were free to breed together.

- Civil War: Many people feared that rabbits would fight and hurt each other if free to roam and interact at will.

- Lack of Defense Against predators: Despite their drawbacks, cages are pretty good at keeping out most animals that want to hurt a rabbit. Would the rabbits become quick prey without the safety of cages?

I decided to build a rabbit colony that realized the above benefits, without attracting the potential downsides. Here’s 6 steps I took to set up my rabbit colony.

Step 1: Build a Rabbit-Proof Fence.

I began my operating by constructing a 50’X30′ pen with wood posts and stock fencing, originating around a 8’x4′ shed. Next, I dug a trench along the interior perimeter and buried more stock fencing 18 inches below ground, filling in the trench with rock-heavy backfill. The buried fence overlapped the above-ground fence for a seamless barrier. Then I overlaid the interior fence with chickenwire to keep the babies from squeezing out between the squares of the stock fencing. It looks like something from the Maginot line:

As extra predator deterrence, I ran an electric fence wire along the top, added a scarecrow, some blinking predator eyes, and some 3D birds. I also use a solar cellular game camera to watch them when I’m out of town:

Step 2: Choose the Right Breed of Rabbit

I wanted to get the type of rabbit that is best suited for colony raising — a rabbit that’s social and chill, to avoid riots and civil disturbance in my colony. After a lot of research, I opted for the American Chinchilla. The American Chinchilla is considered a great meat rabbit, and they tend to get along well with each other, fostering a harmonious colony environment.

Step 3: Decide on Colony Structure:

You need to determine whether you want to keep does and bucks together or separate them. Keeping them together has the advantage of not requiring two separate colonies with their own independent infrastructure. However, if you keep males and females together, you won’t be able to control breeding.

I decided to risk keeping everybody together. To mitigate risks, I started with a breeding trio of one buck and two does. This splits the attention of the buck and gives each doe a break while the buck pays attention to the other. To prevent inbreeding of offspring, I harvest my rabbits pretty early — around 10 weeks — before they’re at risk of having a genetically damaged liter.

I closely monitored my colony initially to make sure this would work. Fortunately, I was lucky enough that my buck is pretty chill and does not harass the does 24/7. Neither does he go after the younger rabbits. This might be normal, or I might have just gotten lucky. If this changes, I’m ready to put him in his own pen, but I haven’t needed to do so yet.

Step 4: Provide a High-Capacity Water Source

The whole point of permaculture is agriculture without the constant need for human intervention. I didn’t want to be bringing my rabbits water every day — I wanted them to have their own renewable water supply. Since I don’t have a stream, I opted for a rain water collection system. I set up a 50 gallon rain barrel that collects water from the rabbit’s shed, and feeds a row of rabbit watering nipples.

This works great late spring-early fall. Once it drops below freezing, I have to use 32 ounce heated water bottles from Tractor Supply:

These DO require filling every day, but at least it’s just during the coldest months.

Step 5: Supply a Long-Term Feeding Solution

Similarly, my goal was to avoid filling the rabbit feeder every day. To accomplish this, I got a Moultrie 30-Gallon Tripod Deer feeder. Then, I modified it by removing the bottom legs, and burying the top legs until the three feeding ports are just over the ground. The three feeding ports are just the right size for the rabbits to get their heads in and help themselves:

The 30 gallon drum can easily hold a 50 lb bag of rabbit feed, and this can last the rabbits for weeks.

I was a little worried about them overeating or wasting feed, but this hasn’t happened — my rabbits seem to self regulate, and only eat when needed. They probably eat more than rabbits with carefully rationed portioned — but I have to work less, so I’ll call it a win.

Step 6: Have a Plan for Butchering/Meat Processing

Don’t be caught without a plan when you suddenly go from 3 rabbits to 20 rabbits. Unless your colony is huge, you won’t be able to support that many adult rabbits, and you need to be ready to process them at about 10 weeks, or when they reach 3-5 pounds. It can be sad and hard to kill a fluffy bunny, so familiarize yourself with humane slaughtering techniques, and be sure you have it in you before you start. If you find you’re unable to kill Peter Rabbit, you’ll be in a situation where you need to offload rabbits fast before they overrun things, and while there’s a healthy demand for rabbits, it ebbs and flows. Craigslist may not be there to help you when you need it.

What to Expect/My Experience

My rabbit colony is about a year old. When I first introduced my breeding trio together, the does got pregnant right away, and in a month, I had 16 bunnies. I lost one, sold one, and ended up harvesting 14. I got about 20 pounds of meat from that first litter, which is almost as much as you can get from a goat or lamb that takes significantly longer to mature. It’s very similar to the yield from meat chickens — but in my experience — was significantly less work. Chickens don’t have great housekeeping habits, and chicken coups needs to be mucked out regularly. My rabbits, on the other hand, rarely poop in their shed, and are very good housekeepers. After a year, I haven’t had to clean anything. To me, that makes them significantly more profitable than chickens.

After the first liter, the does got off track, and now their liters come on alternating months, which gives me a little breathing space so I’m not constantly butchering. Approximately every other month, it’s time to harvest, and rabbits have been our predominant source of white meat — we only occasionally eat chicken any more.

My 50 gallon water source and 30 gallon feeder have worked great, giving me the flexibility to leave the rabbit colony for days at a time — in the fall, we went on a family vacation for 10 days (monitoring the rabbits with a remote camera), and they were fully self sufficient while we were gone, feeding and watering themselves.

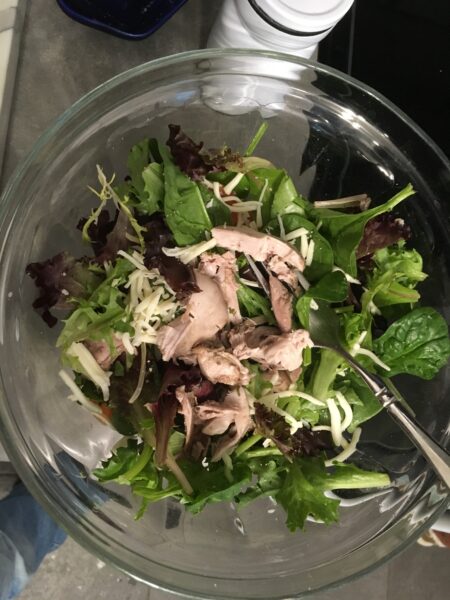

When we’re around, the rabbits love to reduce the cost of their feed by eating kitchen scraps:

. . . or even cuttings from bushes, weeds, and garden leftovers!

So far, it’s been one of my most successful agricultural operations. If you’re looking for a homesteading win, consider a rabbit colony!