The BAREBOW! Chronicles: The Changing of the Guard

Dennis Dunn 02.27.14

It was at the 1983 biennial Pope and Young Convention that Jeanne and I first heard anybody discussing hunting Dall sheep with a bow and arrow. Having met two years earlier at the previous P-and-Y confab, we were only now beginning to expand our imagination over the virtually limitless bowhunting possibilities that were “out there.” Montana archer Paul Brunner had taken a beautiful Dall ram the summer before with Greg and Fay Williams of Nahanni Butte Outfitters. He’d been hunting the Liard Range in the southwest corner of the Northwest Territories, and he couldn’t say enough about what a great operation the Williamses ran, how spectacularly rugged the mountains were, and how awesomely beautiful those Great White Sheep of the far North were.

July 15, 1984, was the first opening Greg had for us. At least that gave us one more year to save up our funds and our vacation days for what we both felt was truly likely to be the hunt of a lifetime. Ours was to be the first hunt of the new season, and Greg had promised to assign us his two best sheep guides.

When July of ’84 finally arrived, Jeanne and I were so ready we could hardly stand it! We’d been told it would be a very rugged, backpack-type hunt, so we had been working out and running nearly every day for a month to get in “sheep shape,” as the hunting world likes to call it. There is absolutely no disagreement out there about the fact that the hunting of wild sheep and goats (anywhere in the world) is by far the most challenging and physically rigorous of all types of hunting. Those creatures simply live in the wildest, most remote, most vertical environments on the face of the planet.

Opening morning of the sheep season dawned clear and calm for us. Jeanne and I had arrived at Nahanni the prior evening. The plan was to fly us and our guides (one at a time) into an old cut-line near the south end of the Liard Range, where Greg had determined he could land his Cub—barring an unfriendly crosswind. The landing and takeoff were both tricky, and it was going to require four separate flights from Nahanni to get all of us and our backpacks in to the point where we could begin the three-day trek that would take us to our principal spike-camp.

Earlier in the month, helicopter drops had been made into the heart of the range: a wall-tent and a couple of steel barrels containing our two-week food supply. Fortunately, the barrels proved to be bear-proof; the wall-tent did not. When we finally arrived at the site, late in the afternoon of the third day of strenuous hiking, we discovered that a grizzly bear had torn the big tent to shreds with his sharp claws, rendering it unusable.

The first day’s hike was the least pleasant, since we weren’t up in the mountains yet and it was nearly all bushwhacking—probably five or six miles of nearly nonstop bushwhacking before we started gaining enough elevation to give us some relief!

By 4 p.m., a spectacular storm was bearing down upon us, and before long the rocky ramparts above us were totally obscured by the black clouds and heavy moisture content that slammed into us with considerable ferocity. Just as quickly, it seemed, old Sol suddenly broke through the gloom, and the skies began to clear.

The knife-like crest of the range still hovered in the mist 1,000 feet above us to the west, but just to the east, an enormous, 180-degree rainbow burst upon the scene with the most intense, dazzling display of colors I had ever witnessed anywhere. All rainbows are beautiful, of course, but some more than others. This one had to be the ultimate rainbow of my lifetime! Not only did it have a pot of gold at either end, but directly underneath its lofty arc—on an open, grassy bench some 200 yards below us—we spied a large grizzly walking slowly away from us through the still-falling rain. Making lazy circles in the air above him (yet still beneath the shimmering, bejeweled archway) was a mature golden eagle that soared, glistening in the sunlight, seemingly intent on following the meanderings of his fellow carnivore. The image of that scene is one that none of us will ever forget.

It was about 4 p.m. on the second day by the time we reached the first helicopter food-drop. The barrel was found to be intact, and it lay just feet away from a tiny seep-hole in the moss where we could replenish our exhausted water supply. On top of the Liard Range, sources of water are few and far between. Some days, in fact, we were dependent on finding one of the relatively few remaining little patches of snow that had not already vanished into summer. The plan was for us to spend our second night at this seep, because there was a small, grassy flat right there, just wide enough to accommodate our two fly-tents.

A third, strenuous day of backpacking finally brought us, by late afternoon, to the site of the second barrel and the “wasted” wall-tent. Since the big tent was unusable, and these items lay at the bottom of a green basin some 800 feet below the ridge-crest, we decided not to make camp down there, and to relocate our food-cache back up on top of the chain. That way, we’d be able to access it more easily in the days ahead, as we hunted in both directions up and down the mid-section of the range. The decision involved emptying out our packs and making an extra trip up to the crest and back down, but the job was accomplished in a couple of hours. By sunset, our fly-tents were up once again, and the high-pressure cell seemed to be establishing itself for as far as one could see.

Alan was to be Jeanne’s guide; Bob accepted me as his challenge. From then on, we always parted company every morning to go off hunting in different directions. The system worked well, and it definitely increased the odds of at least one of us getting a ram.

Day 11 was the day when everything was destined to come together for me. Jeanne and Alan had initiated several stalks, but nothing had yet worked out sufficiently well to give her a shot opportunity. The night preceding my kill truly turned out to be Mussorgsky’s Night on Bald Mountain, and I feared for a while we might never get to day 11. Shortly before midnight, our camp was hit by the most frightening thunderstorm Jeanne or I had ever experienced. Usually, we humans observe mountain thunderstorms from down in the valleys, at relatively safe distances. On this particular night, we found ourselves right in the middle of Zeus’s private quarters as he waged all-out warfare against his enemies in the Kingdom of Cumulonimbus.

Lightning bolts started striking the high points on either side of our saddle every 10 to 20 seconds. The intensely-polarized, peak-to-peak combat continued for nearly an hour, with thunderclap and lightning flash occurring simultaneously throughout much of that time. Before, during, and after the spectacular fireworks, which repeatedly lit up the interior of our paper-thin tents like 1,000-watt floodlights, winds with gusts that had to exceed 100 miles an hour battered our pathetic little shelters relentlessly.

Just at dusk, we had noticed the angry storm coming our way, but it was—as yet—many miles distant. Alan, I suspect, had an idea of what was in store for us, and he insisted on piling an extra hundred pounds (or more) of large, flat rocks on top of every single guy-line attached to each of our tents. I’m convinced that Alan’s foresight was the only thing which kept the four of us from becoming airborne and being blown right off the mountain while still inside our tents!

Somehow, by the grace of God, our tents did not come apart at the seams overnight, and dawn arrived with utter calm and nary a cloud in sight—as if it were the perfect Easter Morning. No doubt we were all feeling washed clean of our sins, and ready to follow the Master anywhere. Many prayers had been said in between the countless thunderbolts of our nocturnal ordeal.

Still a bit traumatized, we were rather slow getting going that morning. Time was running out, however, and Bob and I shouldered our daypacks, resolving that we would not let another 12 hours pass without harvesting one sheep. The peak we chose possessed two different summits, about 150 yards apart. Eleven a.m. found us no farther than 200 yards away from the closer of the two—with no fewer than seven mature rams congregated on top of the rounded granite dome.

Within minutes, I began scaling (with bow slung over my shoulder) one side of their fortress, hoping to catch them unawares at close range. I had forgotten, however, to consider fully the air movements around me. The prevailing breeze had not been blowing up the cut I’d used to reach the bottom of the summit rock, but the granite face I needed to climb was already warm from the direct morning sun, and it was undoubtedly those rising thermals right there which wafted my scent straight upward and alerted my quarry to the danger at hand. I should have known better than to try that approach.

Ever so slowly, I lifted my eyes above the top edge of the rock wall I’d just mounted—only to see that the dome had been completely vacated. As I then looked in the only direction they could have gone to make their escape, I suddenly realized that they had merely relocated to the peak’s other summit. There they were, all seven, standing out as dazzling white silhouettes against the azure sky, just staring at me! Their super-keen nostrils had not let them down, but I think the chances were good that they had never encountered human scent before. To play it safe, however—in the event they had seen human hunters in previous summers—I was determined not to give them any vertical profiles. Staying flat against the rock surfaces, I crawled the rest of the way up onto the cap of the dome, rolled over onto my back, and commenced a long, slow “scoot”—feet first—down off the dome toward the dirt margin of the green earthen swale that rose from below to separate the two summits.

The band of rams seemed utterly fascinated by the spectacle I was creating. I’m sure they’d never seen anything like it before. Once fully descended from the elevated dome, I flipped back onto my stomach and immediately perceived what my new game-plan had to be. Uphill to my right, the seam between Mother Earth and solid rock extended in a straight line about 40 yards to a tiny, grassy saddle I could just make out profiled against the blue sky beyond. If I could manage to gain that saddle and disappear over it, without spooking the rams, the ball game would likely be mine. I would then be able to move—sight unseen—around to the backside of the other summit, sneak over the top, and shoot one of them in his bed. My immediate challenge, though, before I could ever get them bedded, was to put their fears to bed, and to get them to stop worrying about me. I was in full view of all 14 eyeballs, every one of them still riveted upon me.

So, I decided the best strategy was simply to take a nap! One thing I knew with certainty was that—unless I spooked them off the crest of that mountain—they weren’t going anywhere until dusk. My first nap lasted only 20 or 30 minutes because of the building heat. I awoke bathed in sweat. Whereas my stomach lay on the ground, my right shoulder was all-but-touching the hot rock surface, which was performing like the inside wall of a reflector-oven. I felt as if I were being baked alive! (I found out later that the temperature in Fort Nelson on that date had soared to 93 degrees.) The good news, upon my awakening, was that six of the rams had bedded, were chewing their cuds, and were gazing everywhere else but at me. The one ram still standing appeared to be the biggest of the lot, and he had obviously assigned himself sentry duty. His eyes were still glued to me—and for the next two-and-a-half hours, as well!

That’s how long it took to finish my snail-like “snake-slither” over those last 40 yards to the grassy saddle. Dragging my bow uphill behind me with my left hand, I progressed ever so slowly—maybe two inches at a time. The slower my overall pace, the less chance there would be of spooking the sentry ram. Somehow, under the circumstances, I knew that patience was going to determine everything. Unless the sentry’s level of comfort with my presence increased significantly, I knew I’d have no chance at all of achieving my goal. Consequently, a couple of additional naps along the way proved useful, if not imperative.

Slowly but surely, as the afternoon wore on, I was becoming severely dehydrated. I hugely regretted leaving my daypack with Bob. He certainly didn’t need two water bottles, but I did! When the saddle was finally no more than five feet away, I decided—as a matter of strategy—to postpone my last leg of the “snake-slither” for about 15 minutes. Granted, the length of the time-delay was arbitrary, but I used my watch to make it happen accordingly. Sunset was still hours away, and time was the greatest ally I had. If I’d known Bob was waiting for me, water bottle in hand, just out of sight beyond the saddle, I doubt I would have opted for that final “time-out.” It was probably a good thing I did, however.

Although too miserably hot and thirsty to sleep anymore, I was starting to feel excited because I knew I was about to find out if my game-plan was likely to pay off. On this particular marathon stalk (the longest, most difficult, and most exceptional one of my life), the real “moment of truth” would come in the first 60 seconds after the sentry ram lost sight of me. I was certain of that beyond a shadow of a doubt.

Any animal of prey feels more or less in control of a situation, as long as it can keep a potential predator in view. Once your quarry loses visual contact with you, however, one of two things will always happen. Either the prey animal forgets about you (rarely), or it starts worrying about where you’re going next (most common) and quickly decides to relocate to safer, more distant environs. Had I been patient enough? Had I taken enough time to travel those 40 yards? That was the paramount question.

As soon as I slithered out of sight (ever so slowly) over the top of the grassy notch, I regained my feet and heaved a huge sigh of relief. Bob greeted me with a big smile and an outstretched water bottle. It sure felt good to stand up again! Before taking that first precious drink, however, there was one, even higher priority. I removed my baseball cap, gave the sentry another few seconds to forget about me, then rose up (with extreme caution) to “part the grass” with my binoculars. When I saw that the big ram had returned to the others and just bedded down, my heart jumped for joy. I now felt confident that a ram would fall to my arrow before evening. A different ram had risen to become the new sentry, and he wasn’t even facing in my direction!

The second summit was quite different from the first. It was a flat, grassy tabletop which had a second bench 20 feet below it on one side. All the rams but one lay bedded on the lower level, right up against the vertical wall that supported the mesa-like summit. The new guard-ram seemed to have taken up his position about 20 yards out from the others.

The final moment of truth was now nearly at hand. As I crawled up onto the back edge of the mesa, my first concern was to determine once more the exact position of the sentry. It didn’t take me long to spot the top of his horns, and—like all good lookouts—he was facing the only direction from which he and his compatriots were vulnerable to ambush. The grassy tabletop seemed about 20 yards wide and 15 deep. I noticed right away an open, six-inch-wide fissure that started on the front edge of the drop-off and extended toward me some eight or nine feet. Leaving my bow behind for the moment, I eased forward on my belly till I could peer down through the closed end of the narrow crack. Bingo! My line of vision, as it angled down and forward into the sunlight, encountered two big patches of snow-white fur. The rams were bedded right below me, and my shot would be no more than seven or eight yards. I could hardly have asked for anything better!

Retreating to my bow, I sat up, got my knees under me, nocked an arrow, and prepared to shoot. First, however, I needed to advance—caterpillar-like—as far as I could toward the front edge of mesa, without being seen by the guardian ram. When the top of his horns materialized again at the bottom margin of my restricted field of view, the only thing left for me to do was draw my bow, stand, take two steps forward, lean over, and direct an arrow at whichever ram was offering the best shot opportunity. The standing part was vital, unfortunately, because having to shoot almost straight down made a kneeling position out of the question. There’d have been no room for the lower limb of my bow!

As soon as the sentry spotted me getting to my feet, he stomped a front hoof and went into motion. Immediately, all the other rams began rising from their beds. As I started to take aim at one of the two directly below, a movement several yards off to the right caught my eye. I glanced that way and suddenly realized I was looking at the original sentry-ram: the leader of the band, the biggest of the seven, and the one I’d been hoping to harvest all day long.

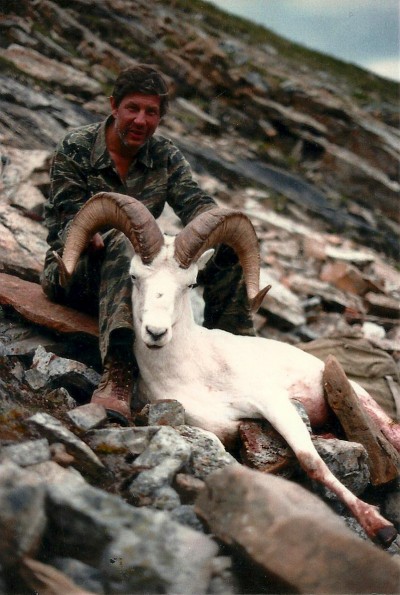

But time on the shot clock had run out! My arrow left the bow with zero seconds remaining. It was launched by the pure instincts of the primordial predator pulsating within me. Although I had shifted targets at the last possible moment, I’d had no time to aim the arrow consciously. When I saw the shaft pass through the ram somewhere amidships and self-destruct on a rock just beyond, his four feet were already under him, and his body was twisting toward the only “escape hatch” they had available to them. I quickly sent a second arrow after him as he ran full-tilt down the ridge away from me, but the missile landed harmlessly in the rocks, right between his flying heels. I knew, however, the first shot would prove fatal; it was simply going to take some time.

Bob and I watched the fleeing band of rams as they turned left off their escape ridge 300 yards down the mountain and headed across a large, steep section of smooth, boilerplate rock. They all slowed down for this traverse, but their leader was now bringing up the rear. When the wounded ram reached the middle of the boilerplate, he stopped and stood there, unmoving, for a good 20 minutes. Through our binoculars, we noticed a big reddish stain developing on the rock surface beneath him. The other rams had now stopped, as well, but they were all out there 50 to 100 yards ahead of him, nibbling on various pockets of greenery.

Eventually, when my ram decided to finish traversing the steep rock plate, he bedded immediately on top of a tiny alpine nest-spruce. Meanwhile, Yours Truly was suddenly not feeling very well, as the delayed effects of heat prostration were beginning to hit me. Since I could see my ram wasn’t going anywhere, I lay down on my back on a flat boulder that allowed me—with my head cranked sideways—to keep one eye on the stricken animal. My heart had switched into fibrillation mode and was racing wildly out of control at something over 200 beats a minute. For a while, I felt so light-headed I feared I might pass out.

During the next three hours, the wildlife drama that unfolded before our eyes was one of the strangest (and most moving) I have ever witnessed over my many years of exploring the wilderness regions of North America. I had shot my ram around 4 p.m. At 5 o’clock, he got up from his initial spruce-bed and advanced 20 yards to a softer, moister patch of green. Half-an-hour later, he switched ends in that bed. At 6 p.m., he rose and advanced one last time, perhaps 10 more yards, to an even-friendlier-looking spot of green, no bigger than a bathtub. In short order, it was to become his deathbed.

First, however, it seemed that the changing of the guard had to take place. Over the next two hours, his six brethren—one by one—from distances as far away as 700 yards, all came back to pay their respects and bid their old leader a final good-bye. Absolutely spellbound, I watched as each ram, in turn, arrived at his side and then proceeded to nuzzle him, nose-to-nose! It was clear that every one of the six understood that he would not be with them much longer. At the conclusion of each individual adieu, the deliverer turned away and fed off into the setting sun. The last of his colleagues to come and pay tribute (with the same nose-to-nose nuzzle) was the second-largest ram in the band. No doubt he would become, by natural selection of his peers, their new leader. When this last one finally turned to go, my ram tried to regain his feet and follow. The monumental effort went for naught. No sooner had he managed to stand, than he died on his feet—collapsing back into the bed he had struggled so valiantly to leave. The Ceremony of the Fraternal Farewell was complete. And so was the changing of the guard.

Now that I think of it, there were two “changings of the guard.” The first one (a new sentry) had made possible the second (a new leader). Undoubtedly, without the first, the second would never have taken place. What an odd irony!

As the reader can well imagine, many emotions had coursed through me while I watched this powerful drama. In the world of Ovis dalli, there was apparently a much-more-highly-structured social order and protocol than I would ever have believed. I felt in awe of being allowed to observe such a moving piece of Nature’s theater, and I felt an overwhelming sense of gratitude to the Almighty, Who had spared my life the night before, yet allowed me—as a natural predator in the food chain—to take the life of such a magnificent animal fewer than 24 hours later. For every man or beast, life hangs only by a thread!

Editor’s note: This article is the eighteenth of the BAREBOW! Chronicles, a series of shortened stories from accomplished hunter and author Dennis Dunn’s award-winning book, BAREBOW! An Archer’s Fair-Chase Taking of North America’s Big-Game 29. Dunn was the first to harvest each of the 29 traditionally recognized native North American big game species barebow: using only “a bow, a string, an arrow—no trigger, no peep sights, no pins—just fingers, guts, and instinct.” Each of the narratives will cover the (not always successful, but certainly educational and entertaining) pursuit of one of the 29 animals. One new adventure will be published every two weeks—join us on the hunt! You can learn more about the work and purchase a copy on Dunn’s site here. Read the seventeenth Chronicle here.

Top illustration by Hayden Lambson