The BAREBOW! Chronicles: The “Hail Mary” Ram

Dennis Dunn 08.30.14

November, 1994. I had not yet been bitten by the Super Slam bug. The idea of trying to harvest with my bow one of each of North America’s 28 big game species still had not infected the tissues of my brain. That was not to happen till 1998. On the other hand, the dream of taking the so-called Grand Slam of our continent’s four wild sheep was now well on its way to becoming my first, true hunting obsession. After arrowing my Dall ram in 1984, and my Stone ram in 1993, I was praying that the Rocky Mountain bighorn hunt I had booked with Alberta outfitter Rick Guinn would be successful—thereby getting me three-quarters of the way to the sheep Grand Slam. Only the desert bighorn would then remain. By 1994, only nine bowhunters had been able to lay claim to an archery Grand Slam. Prior to 1985, nobody had ever done it.

Thus did I arrive in late October at Rick Guinn’s lovely home in the Kananaskis Valley with high hopes, though rather modest expectations. I knew the challenges were going to be formidable, to say the least. My good friend, Tom Taylor, from Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, had booked the hunt with me early in the year at the annual convention of the Foundation for North American Wild Sheep, and we were both looking forward to a great adventure together. For each of us, it was to be our first try for the species.

I believe that back in the mid-1990s, the late Canmore bow-season for sheep consisted of eight nonresident tags and 50 resident tags. Tom and I had Rick’s only two tags for that 1994 archery season. The “greater Canmore” bow area lay just north of Trans-Canada Highway 1 and was separated into several major drainages coming off the south boundary of Banff National Park. The easternmost was the Exshaw Creek drainage, and that was the one where we would be hunting.

Since the drainages came right down to the big freeway and all contained choice wintering habitat for the sheep that harsh weather conditions were already beginning to push down out of the park, Alberta Fish and Wildlife had established a strict no-hunting zone for a width of one kilometer north of the frontage road that paralleled Trans-Canada 1. This still meant, however, that the 50 lucky residents with tags from the annual lottery draw had very easy access to Guinn’s hunting area. We knew in advance, therefore, that we would have lots of local competition for the rams leaving the safety of the park. The one great thing in our favor was the fact that just getting to Rick’s base camp required a hike of a good eight miles. Notwithstanding the certain advantages that fact gained us, Tom still had a couple of stalks ruined for him during the 21-day hunt by resident bowhunters.

The outfitter had made arrangements for our hunters’ duffel bags to be helicoptered in to base camp. Rick had chosen Kent Maxwell from Rocky Mountain House, Alberta, to be my guide. Tom’s guide was to be Wes Kopas (also from Alberta), whom I had met 10 years earlier when he was guiding for Greg Williams at Nahanni Butte in the NWT. For the long hike in, I carried my daypack and my bow case in hand—grateful for one more day of not-too-strenuous exercise to help me get in shape, before the really tough climbing began the next morning. When Kent and I reached the two double wall-tents that were to serve as our home for three weeks, Tom and Wes were already there to welcome us. They had hiked in earlier in the day.

Situated and well-hidden on the last flat piece of ground surrounded by dark timber as you moved up the Exshaw Creek drainage toward the headwall, base camp put us only 20 minutes by foot from the base of that headwall, and less than an hour away from the saddle in the high mountain ridge that crossed over the top of the headwall. Beyond the saddle, less than 1,500 yards distant, lay the boundary (often obscured in fog) of Banff National Park. Since Rick’s outfitter-unit came to an end right at the saddle—and essentially at timberline, as well—more than once during the hunt we felt sorely tempted by the many rams in full view which we were sometimes able to spot out there in “no man’s land,” between the two boundaries. Once in a while, they would cross over our saddle, but more often they would cross higher up on the massive mountain ridges that powered their way skyward into the clouds on either side of the saddle. Only a few days of decent weather during the entire hunt presented us with a complete panoramic vista of the rugged Canadian Rockies that surrounded us.

The rest of the time, conditions were overcast, gray, windy, snowing, occasionally a whiteout, and (almost always) bitter cold. Average daytime temperatures hovered around zero degrees Fahrenheit. Fortunately, I had packed well for the hunt, knowing what I would likely be dealing with. “Just to be safe,” Rick Guinn had advised, “come prepared to cope with 30-below temperatures. And maybe high winds simultaneously.” Like most of the other slopes in the area, the Exshaw Creek headwall was extremely steep. Covered with snow, the autumn grasses underneath were a major attraction for the sheep, but a human passage across the headwall in winter conditions was unthinkable without the steel crampons we carried with us every day. We used them frequently. Absent those strapped to your boots, you were just asking to become a human toboggan!

Before continuing any further, however, I absolutely must beg the reader’s indulgence and take you back to something that occurred a couple of years earlier, during an unsuccessful moose hunt in the NWT. When I arrived in mid-September at Nahanni Butte, Greg Williams greeted me with bad news—he said I’d be unable to hunt for a few days, until he could come up with a guide for me. The problem was he’d just had one quit on him the night before, and he’d had to fire another that very morning. I could either stay at Nahanni with his wife and kids, he explained, or he could fly me with his Super Cub out to moose camp, where I could still hang out with the other hunters as they came and went. Once success freed up one of his guides, then I could start hunting legally.

The choice was a no-brainer for me, and by early afternoon Greg set me down on the grassy little bench which a few strokes from an ax had turned into the nearest local airstrip. Now—to reach the important point of this digression—I must explain that I almost never embark on a wilderness hunt without packing a small, lightweight practice-target of some kind. In this instance, I was extremely glad I had, since it gave me a fun way to kill time until I would finally be able to start hunting with my own guide.

For several hours a day, for four days in a row, I turned Greg’s airstrip into a long-distance shooting range. My target was a 16-by-16-inch-square piece of rubberized Styrofoam. To give myself plenty of exercise and to make the challenge really difficult, I paced off exactly 150 yards on the long axis of the grassy bench. With the toe of my boot, I dug a target line and a shooting line in the dirt. Every single one of the hundreds of arrows I shot over those four days was fired at that same absurd distance. Just for fun—and to keep boredom at bay.

Amazingly, despite investing an inordinate amount of time and effort in the attempt, I never did hit that darn target! Not even once! It eventually got to be very frustrating, as countless times my arrows seemed to be missing by only fractions of an inch. Again and again, in walking up to the target, I would find an arrow lying right under it in the grass–with the fletching out in front and the point behind. I even “skitched” a few arrows off the sides and top of the target, but I never actually succeeded in “skewering” it. Before long, the challenge had become an obsession. I think the only thing that saved me from insanity was suddenly discovering that I finally had a guide all to myself.

Well, we return now to the bighorn sheep hunt of November 1994. After 10 days of futile or blown stalks, the 11th day dawned sunny and bright. It was a welcome relief from the weather we’d been having. Kent Maxwell and I got a reasonably early start, and, no sooner had we hiked far enough up the drainage to break out of the last bit of timber than we immediately spotted two mature rams feeding a good 2,500 feet above us, at the highest possible margin of the vegetation line. They were just below the cliffs that led up into the uninhabitable world of Icy Nowhere. I knew it would be an arduous climb up the steep, snowy slopes, but I also knew that that was what I was there for.

By 11 a.m., we had gained the elevation we thought necessary. Kent suddenly turned his back to the mountainside we were on and began studying the one across the valley with his binos. All at once, I heard the words “Quick! Take your pack off and put an arrow on your string!” Knowing better than to ask why, I simply did as instructed. Kent went on to whisper to me that he had spotted Tom’s guide, Wes, across the valley, frantically waving his arms and pretending to shoot an arrow from an invisible bow.

“Those two rams must be pretty close to us, the way Wes is gesticulating,” said Kent. “Be ready to shoot in a hurry, and just pussyfoot your way over the top of that hogback right above us.”

I was sweating like a barbecued piglet after the long, hard climb, but a few slow, deep gulps of the thin air helped to stabilize me some, and I started upward with my heart in my throat—not knowing what to expect, other than excitement encapsulated within the space of a few short seconds. Were the two rams just out of sight over the rise that topped out only a few feet above me? I would know momentarily.

The first thing my eyes encountered as they crested the little slope I was on was another little hogback 20 yards past the first. There was nothing in view between the two, but since I couldn’t see over the second one, I kept pushing forward—ready to draw at a moment’s notice. That proved wise.

Suddenly, as my eyes were able to look over the second crest at what lay beyond, there they both were—right in front of me, staring at me in disbelief. The extent of their incredulity is probably what allowed me to draw and get the shot off before they went into motion, but my arrow passed a tad too low, right behind the forelegs of the ram that just happened to be the one offering me a broadside shot. His legs had been cut off visually for me by another hump of snowy terrain between us—thereby making the distance look closer than it really was. I suppose I shot it instinctively for something like 35 yards. In reality, it may have been a bit over 40.

Immediately, my quarry bolted for the cliffs above, and within seconds all was quiet. It was as if they had never been there at all, save for the tracks left in the snow. My heart was pounding like a tom-tom drum, and I was kicking myself for not having held a little higher on the shot. When Kent and I joined up again, he spelled out a new game plan that he said had worked for him several times before. The highest patch of green on our side of the valley lay just 30 yards above us. It was a triangular configuration of alpine spruce trees that stretched 20 yards up the mountain to a sharp point and had a straight baseline running about 15 yards across the steep hillside. Kent suggested we bury ourselves in the middle of the spruce patch and just hang out there for the rest of the day. By late afternoon, the rams would probably come back down out of the cliffs, and maybe feed right past us on the dry-grass stubble under the snow. The scenario sounded plausible to me, so that’s what we decided to do.

About 30 minutes after we’d ensconced ourselves in the handy hideaway, the sky covered over, and a strong wind came up that buffeted us mercilessly for a good two hours. Combined with zero-degree temperatures, the gale made my down parka feel like a T-shirt. By 3 p.m., the wind had decided to take its rantings elsewhere, and the sun decided to return for a most welcome, pre-dusk, golden curtain-call. We had certainly appreciated its lovely performance in the morning. Around 3:30 p.m., our two rams suddenly materialized right above us at 150 yards and bedded down on a little crown of ground where our ridge met up with the neighboring ridge.

Unfortunately, when the duo got up to start their evening feeding in a downhill direction, they chose to descend the gentle crest of the other ridge—not ours.

For nearly an hour we watched helplessly as the two trophy rams finally reached our elevation and then continued to diverge farther and farther away from us on their way down the mountainside. By the time the sun slipped below the horizon, the air was dead calm, and it became crystal clear that our quarry had no intention of crossing over onto our ridge. Suddenly, a strange thought penetrated my cerebral cortex. The two rams were feeding side by side, as if joined at both the hip and the shoulder. They were facing dead away from us. I looked at Kent and asked him a question: “How far away from us do you figure they are?”

My guide thought about it for a bit and then replied, “Oh, I don’t know. Maybe 150 yards, give or take 20 either way.”

“You know, Kent,” I continued, “I’ve got a weird feeling I can hit one of those rams, if they will just stay like that—glued together.” I proceeded to tell him of my intensive target practice, for several days in a row, at a carefully-measured 150 yards while marooned in moose camp a couple years earlier.

“I learned just what part of the middle of my wrist has to block out the target at full draw, in order for the arrow to have a chance to hit it at that distance.” The look Kent was giving me made me wonder if he thought I was pulling his leg in jest.

“I’m dead serious,” I insisted. “As long as those two keep standing in that position, like Siamese twins, I think I might have a darned good chance of skewering one or the other. And—since we’re much higher, and they’re facing straight away—any arrow coming down on them from above and behind will either miss completely, be a very superficial hit, or be an absolutely lethal one.”

“Go for it, Dennis!” were Kent’s last words on the subject.

The light was beginning to fade quickly now. As soon as we stepped out of the spruce thicket into the open, the rams became aware of us. Perhaps they had known of our presence all along. The eight legs, however, stayed in place, unmoving, while their heads rubbernecked around to stare back at us over their rumps. I still had a double target to shoot at, with a choice of two bull’s-eyes, and I wasted no time in coming to full draw. After moving my bow-hand out to the side and back again several times, I finally released the arrow with a huge hope and a small prayer.

My eyes managed to keep sight of the arrow all the way to where it stuck in the snow about five yards short of the rams’ hind hooves. Instantly, the two shot forward 10 yards and stopped in exactly the same posture—hip to hip, facing straight away, but looking back at us. In watching the flight of my arrow, I’d noticed a “sidehill drift” phenomenon that occurred en route. Because of the modest evening thermals descending toward the valley, the shaft appeared to have slipped a couple feet left during its trajectory. Since the rams were still offering me the same stationary double target, I decided to go to school on the first shot and attempt a second.

This time I held a bit higher and purposely aimed a wee bit to the right to compensate for the effect of the evening air currents. This second shot turned out to be the luckiest one of my life, or what I like to call my Providential Arrow. I know the Hand of God guided it all the way to my bighorn ram; there simply is no other possible explanation. Between the two shots, dusk had further diminished the remaining light just enough so that I lost sight of the second arrow a moment before impact. “Did you hear that?” I asked Kent.

“No, I didn’t hear a thing,” he replied.

“Well, I did!” I said, excitedly. “I’d recognize that sound anywhere! I just know I made a solid hit on one of those two big boys!”

“I think you might have,” responded Kent. “It seemed to me that one of them flinched just as they took off.” I’d already known that Kent’s hearing was slightly impaired, but I also knew his eyesight was significantly better than mine. His words only added fuel to the optimism starting to well up in my breast.

By the time we reached the spot where my first arrow was sticking up out of the snow, a good half-hour had elapsed, and darkness had pretty well established dominion over our alpine surroundings. The steep canyon between the two ridges had been treacherous to cross, choked as it was with ice- and snow-covered rocks. Across the valley, a tall peak was blocking out the timid approach of a nearly-full moon, and we could tell that, before long, the Queen of the Night would force the King of the Night to beat a hasty retreat. That qualified as good news, yet there was even better awaiting us: We were not able to find a second arrow!

Our immediate challenge was to follow the tracks of our quarry and see if the spoor provided any substantiation for our high-flying hopes. About 50 yards along their path, I spotted what we were looking for on the uphill side of their tracks. “Here’s some sign,” I practically chortled, as I massaged some darkish snow crystals between my fingers. “I knew I hit him! I just knew it!”

Kent was now 10 yards ahead of me, and all of a sudden he said, “Dennis! Come take a look at this!” I rushed forward to join him and was overjoyed to see what he was pointing at. Just a foot uphill of where the rams had passed lay a solid, dark line that must have extended at least 30 feet in the direction they had gone. I knew right then there was a high probability we would recover my bighorn.

All of a sudden, Kent asked me if I was hearing some rockfall up ahead and above us. “Let me listen a bit,” I replied. “Yes, I am,” I added, a few seconds later. With that, I raised my binoculars to my eyes and tried to peer into the gloom above me. I knew the cliffs were right there, but I could make out only slight variances between the dark gray and the ubiquitous black. I had no sense of depth perception. Without the binos, everything had looked uniformly black. All at once, I saw motion. A perfectly round black disc somehow stood out against a lighter shade of black, and I watched it for five seconds rising upward on a diagonal before I saw it settle downward a bit, then cease all motion. Game over, I thought to myself. That just had to be my ram!

“Kent!” I whispered excitedly. “I think I just saw him bed down up there. Let’s get out of here as quietly as possible and come back in the morning.” Kent agreed, and we began retracing our steps immediately. In the inkiness, however, the going was slow and the footing treacherous. We soon decided to sit down, finish the last of our frozen luncheon-leftovers, and wait for the moonrise to arrive and render our descent much safer. There were other cliffs below us, so it made no sense to take unnecessary risks which greater patience could reduce significantly.

Even so, once the steep, snowy slopes were flooded with moonlight, it was still no easy trip down the mountain. Nothing is ever easy in sheep country in winter conditions. Nonetheless, the return to camp was completed without serious incident, and we walked into the cook tent shortly after 10 p.m.—heavily sweated, famished, and grateful to be down off the mountain. Tom and Wes had begun to worry, so they were very glad to see our ruddy faces.

“I gather you guys must have had some action up there today,” barked Tom, his eyes gleaming with anticipation. “Any shots?”

“Well, yeah. More than one,” I responded slowly.

“Did you kill a ram?” Tom wanted to know, more insistently.

“Well, we think so,” I answered. “We’ll know for sure in the morning.”

“For God’s sake, Dennis! Stop holding back on us! Tell us the story,” exclaimed Tom impatiently. “How long a shot did you make on him?”

“I think I’ll defer to Kent on that,” I said quietly—feeling very humble, and not at all comfortable with the last question.

“So talk to us, Kent,” Wes chimed in. “How long a shot did Dunn make?”

“Well, I don’t rightly know, boys! I reckon it was probably somewhere between 140 and 160 yards.” A second later, holy, four-letter epithets started ricocheting around the walls of the tent like a covey of trapped bats.

Once the blue language had subsided, Tom assailed me with “And you actually think you hit him at that distance?” I nodded silently.

Just then the radiotelephone in the tent rang. Wes picked it up, to find Rick Guinn on the other end. Both sides of the conversation were audible, and Rick was calling to see if his wayward guide and hunter had returned safely.

“They came in only minutes ago,” Wes assured him. “Dunn evidently hit a ram just at dusk, and they decided to leave it till morning.”

“How long a shot did Dunn make on his ram?” Guinn inquired.

“Kent says it must have been at least 140 yards—maybe as much as 160,” replied Wes matter-of-factly.

“Holy ____!” the outfitter shouted over the phone line. “What the ____ did Dunn think he was doing? That’s ________ incredible! Call me tomorrow if you find him.”

Following a delicious, hot meal of moose stew, I buried myself in my sleeping bag and passed a relatively sleepless night—shivering not from the cold but from excitement, and the anticipation of first light. Daybreak came not nearly fast enough, but after a quick breakfast, Kent, Wes, and I struck out for the base of the Exshaw Creek head-wall. Though very cold, it was truly one of those perfect days when the sapphire skies could hardly have held a deeper blue. No sooner did we exit the last of the timber than I looked up at the highest set of cliffs above us, feeling certain my ram was up there somewhere, lifeless and waiting to be found.

The sight that greeted me made my heart skip a beat! “Just look at all the birds!” I exclaimed. There must have been at least 10 large ravens, hawks, and eagles circling in a narrow column several thousand feet above us. What’s more, they appeared to be right above the area where I believed I had seen my ram bed down the night before. Leaning back against the sidehill behind me, I trained my binos first on the birds and then lowered my gaze to the icy rocks directly below. It took me less than 15 seconds to find him. I don’t believe he had ever changed beds again.

“Hallelujah!” I shouted. “I see him; let’s go get him!”

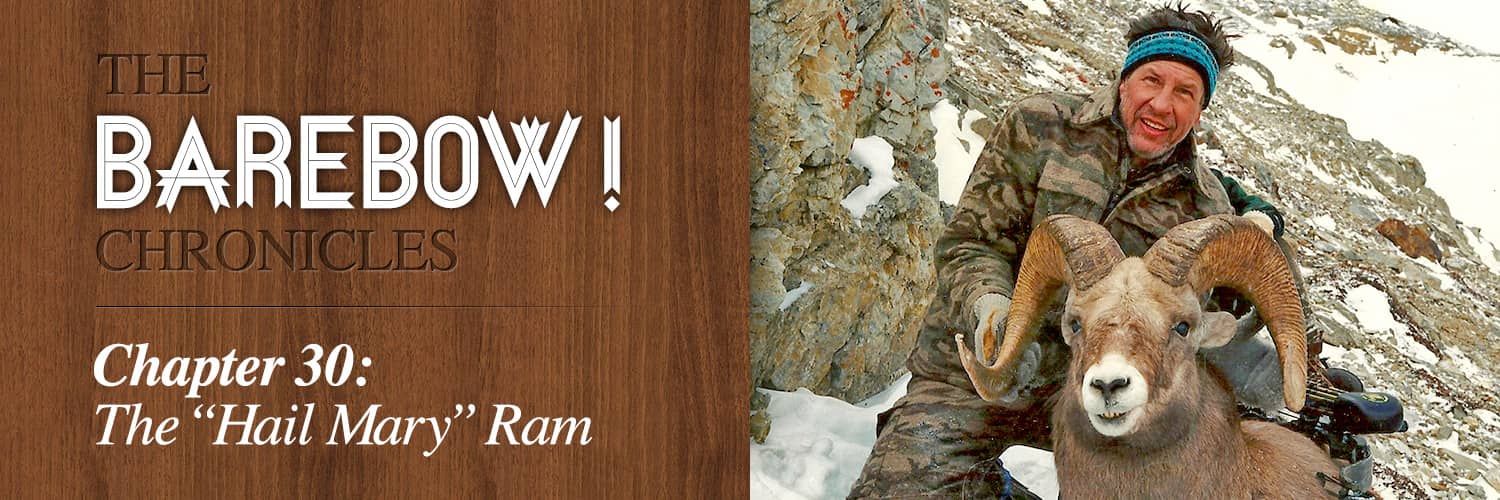

The demanding climb took more than three hours. When we finally reached my ram, we found the arrow protruding from his rump—half in him, half out. The broadhead had entered near the tail, angling forward and down. It had severed the femoral artery in the right hip and then ended up in the abdominal cavity. After a few celebratory photographs, the serious work of butchering and quartering began.

The magnificent animal had died on a tiny ledge no bigger than he was. Sixty yards below his final resting place, a steep, icy couloir disappeared over the lip of a 300-foot drop that was totally vertical, with a huge, open snowfield lying directly below. Once the ram’s head, horns, and cape had been removed, and the four quarters cut clear of the rest of the carcass, we carefully lowered each quarter into the couloir and gave it a fast ski-jump start off the lip into the void below. Kent shouldered the parts of the ram destined for my taxidermist, and the three of us then began a careful, circuitous descent which brought us around—an hour later—to the base of the gigantic frozen waterfall. Not far from its base were the four quarters of sheep meat, all lying within a few feet of each other.

The snowfield lay on a bench that cut across the steep mountainside. Just below it was a second frozen waterfall, and then a third one below that. The huge, vertical columns of ice were no doubt continuations of what, in summertime, would have been a single silver ribbon of snowmelt, falling from the highest, year-round snowbanks near the top of the 10,000-foot peak. The waterfall trick, which had worked so successfully for us with the 300-foot drop, worked just as well on the next two sections of our treacherous descent. Even without an extra 160 pounds of sheep meat on our backs, we encountered several spots where safe passage was anything but a given. In one particular place, a long piece of fixed rope tied solidly to a leaning alpine tree-trunk was all that allowed us to avoid a premature arrival in the Happy Hunting Grounds.

After recovering the four quarters of meat at the bottom of the third drop-off, we tied them to our pack-frames for the remainder of the hike back to base camp. Wes was the youngest and strongest, so he took the two lightest quarters and somehow managed to struggle to his feet. The rest of the trip down was not as steep—just hard and slow. By the time we finally dragged ourselves and our loads through the door of the big tent, it was getting dark, and we were all pretty well exhausted.

Exhausted but happy, I should say! No, there’s a better word. I was downright ecstatic! And several other emotions were flooding through me, also. I was feeling overwhelmingly blessed, as well as thoroughly humbled by the magnitude of my blessings. By any odds a bookmaker might have come up with, I had had no right to harvest my trophy bighorn the way I did. It had been so improbable! Yet, at the moment, it had seemed so doable! If the Good Lord had been trying to reward me, I had no idea why, or for what. Yet, in my mind, there was no way of escaping the conclusion that the second arrow had been providentially guided all the way to its target.

Perhaps! Perhaps it was God’s way of saying something like this to me:

“Dennis, sheep hunting is a young man’s game; you are now in your mid-fifties. You obviously believe in yourself. I want you to believe in Me, as well, and I want you to know that I believe in you also. Press on, ye of middle-age years, who are still so young at heart, and so determined! It’s time for you to take your Rocky Mountain bighorn, and to get serious about moving forward to harvest the desert bighorn I have in mind for you. He was born a year ago last May. You and he have a rendezvous I am planning for December of 1999 in northern Nevada. Just don’t forget to do your part by continuing to apply each year for your desert sheep tag in that state. I’ll take care of the rest—provided you agree never to give up!”

Perhaps!

Editor’s note: This article is the thirtieth of the BAREBOW! Chronicles, a series of shortened stories from accomplished hunter and author Dennis Dunn’s award-winning book, BAREBOW! An Archer’s Fair-Chase Taking of North America’s Big-Game 29. Dunn was the first to harvest each of the 29 traditionally recognized native North American big game species barebow: using only “a bow, a string, an arrow—no trigger, no peep sights, no pins—just fingers, guts, and instinct.” Each of the narratives will cover the (not always successful, but certainly educational and entertaining) pursuit of one of the 29 animals. One new adventure will be published every two weeks—join us on the hunt! You can learn more about the work and purchase a copy on Dunn’s site here. Read the twenty-ninth Chronicle here.

Top image courtesy Dennis Dunn