The BAREBOW! Chronicles: The Paralysis of Fear

Dennis Dunn 01.28.15

As the wounded grizzly came running obliquely toward me, the first thing I noticed about him (other than his considerable size) was the bright red arc he was pushing in front of him in the shape of a galloping, monochromatic rainbow. It was as if the area of his right collarbone had sprouted a garden hose and somebody had turned the water pressure on full blast, aiming the stream forward and upward at a 45-degree angle to the ground.

A few seconds earlier, I had not even been aware of the bear’s presence in our environs. Then, at the sound of Jack’s bowstring some 40 yards away, I suddenly realized my friend had just taken a shot at something, and I jumped to my feet to see what was going on. I was hardly prepared for the sight that greeted my astonished eyes. This was supposed to be a moose hunt—not a grizzly hunt. Yet what happened next turned the affair into what could have become a very grisly grizzly hunt.

The first thought to race through my mind was that Jack’s arrow had obviously not struck the bear where he intended it—and that I’d better try to help him out by placing a second arrow in the beast in a better location!

At the sound of my friend’s shot, I had been sitting on the ground with my back against a small jack pine. I’d been looking out over a huge expanse of meadow, surrounded by old-growth forest. Carelessly, I had made the mistake of assuming that (if anything were to show up in the meadow that evening) I’d have plenty of time to extract an arrow from the rotary, cylindrical back-quiver leaning against a tree right next to me. Now, as the angry behemoth was about to pass in front of me within 20 yards, I was desperate to get an arrow out of my quiver and onto my bowstring. It was going to have to be a quick shot, for sure!

I grabbed for an arrow shaft through the open slot in the bottom half of the quiver, and, as the business-end came out first, the broadhead got hung up in the wild blackberry vines hidden in the grass at the base of the tree! With my recurve bow at the ready in my right hand, I seized the shaft with my left—a few inches above the three-bladed point—and yanked violently. Caramba! The hand-sharpened blades of my Bear Razorhead sliced through the vines, all right, but I had underestimated their cutting power—or else the strength of my yank! The blades kept traveling a ways toward my midsection and proceeded to slice my bowstring in half, as well!

The sound of the bow uncoiling immediately brought the wounded grizzly to an abrupt halt. As the enraged monster turned to face me, he stood up full-height on his rear legs and let out the most savage, bloodcurdling sound I had ever heard. At last, he had found his assailant, and it was time to claim his pound of flesh! Standing in front of one of Mother Nature’s most efficient killing machines with a useless bow in one hand and a useless arrow in the other is not exactly a recipe designed to keep your skivvies clean. I guess the only reason mine didn’t change colors on the spot is because fear had suddenly frozen my brain, and all other parts of my anatomy simultaneously—sphincter muscle included. I don’t think I could have turned and run even if I’d tried! Yet, at least I remembered having read that that was the worst thing you could do, if you didn’t want to trigger a charge.

The only question in my mind, at that point, was Where in thunderation had my guide disappeared to? I hadn’t seen hide nor hair of him (nor his rifle) for three-quarters-of-an-hour! And now it was my hide and my hair that were in mortal danger of being radically and forever altered by a few short seconds of ursine fury!

***

The above situation occurred on the initial evening of my first-ever Canadian bowhunt, back in 1969. My good friend Jack Vandervest was my hunting partner, and, for $400 apiece, we had booked a five-day moose hunt just outside Bowron Lake Provincial Park near Barkerville, British Columbia. The hunt was for bulls only. I no longer even recall the name of our outfitter or guide, but the outfitter had told us there was a lot of game in the area, and we’d been advised to pick up a black bear tag and a grizzly bear tag in addition to our moose tags. As I recollect, we bought two moose tags, but to save money we only purchased one bear tag for each species of bear.

As moose hunts go, it was a total bust. Nary a bull was seen, and only a very few cows. We didn’t reach our remote hunting cabin until late afternoon, so for the first evening’s hunt our guide rowed us across a lake, and we all hiked in a short distance to this large forest meadow with one small, oval-shaped stand of young jack pines in it—about 80 yards out, at the point closest to the forest primeval.

Our guide positioned Jack at one end of the grove, just inside the treeline, so that he would be looking out across the narrow neck of meadow. Next, he positioned me on nearly the opposite side of the jack pines, so I could survey most of the rest of the meadow’s perimeter. The last remark he made before pulling his disappearing act was something to the effect that “after a bit” he might make a tour around the entire big meadow, just inside the forest, and see if he couldn’t “kick something out” in our direction.

But where the hell was our guide, now, when I needed him most?

Suddenly, my heart switched from imitating a bongo drum to doing silent backflips and cartwheels, as a deep voice boomed from the bushes behind me, “Do you want me to shoot him?”

My instant reply was, “No! Not unless he charges!” My thinking was that—given the “red rainbow” I was still looking at in front of me—we might, perhaps, have a chance to recover the bear eventually and preserve it as a bow-kill for Jack. I knew that very few grizzlies had ever been taken by modern bowhunters, and that any bullet hole in the bear’s hide would prevent Jack from being able to claim the animal as an archery-kill.

At the sound of two human voices, the bear made a sage choice (wisdom over valor) and dropped to all fours, continuing the course he had set for himself across the big meadow. Greatly relieved, but disgusted I’d not managed to put a finishing arrow in (or through) the big boar, I headed for my friend to learn how all this unexpected excitement had come about. Thank God our guide had not already started out on his grand perimeter-tour!

Jack’s story was quite something! He had only been in position for a bit over half-an-hour when he saw the bear emerge from the bushes directly across the narrow neck of meadow. It soon became clear the animal was intending to enter our stand of pines at the precise spot where Jack was kneeling. As the bear came within bow-range, Jack kept looking for a shot opportunity, but the grizzly continued walking straight at him with his head down low—thereby blocking any access to the chest. Jack knew he was downwind from the beast, and that all bears are quite nearsighted. If he were to do nothing at all, Jack’s big worry was that the grizzly might practically step on him before becoming aware of his presence! He realized that the carnivore’s reaction (or overreaction, at such close quarters) could well end up permanently rearranging his physiognomy.

“Once he had approached to within 15 yards, or maybe less,” explained Jack, “I couldn’t believe he was not able to hear the sound of my heart trying to bust right out of my rib cage! It was almost deafening in my ears!”

Then, at not much beyond 10 yards, the bear stopped, lifted his head, and turned to look out into the meadow. My buddy waited no longer. The animal’s brisket was now exposed. Jack drew back his recurve and quickly let fly a wooden shaft, tipped with a shaving-sharp Bear Razorhead. Evidently, the shot was off-line slightly and embedded the point of the arrow in the grizzly’s clavicle. Instantly, the bear stood up, broke off the arrow with one swipe of a paw, dropped to the ground, and headed posthaste in my general direction.

Upon retrieving the arrow, we found that only two inches of the shaft were missing on the front end. Our assumption of a hit in the collarbone seemed altogether likely. The arrow was clearly not in the bear’s vitals, yet we knew—given the amount of blood-sign—that we now had an obligation to trail him. The odds were that it was not a good enough hit to take his life, but we would have to find out for sure. The big question was, when should we begin the dangerous tracking job? Within an hour, dusk would be upon us.

The three of us waited for 45 minutes before taking up the trail across the meadow. For 200 yards, it was one you could have followed with your eyes virtually shut: an unbroken red line, like a long string, laid out on the grass. Then there were gaps in the line; and finally—as we neared the bear’s point of entry into the big forest—there were only small patches of red every 15 or 20 feet. As soon as we got into the trees, however, beneath the forest canopy, it was suddenly “night,” and we all knew that trying to follow a wounded grizzly in heavy cover by flashlight was sheer insanity! Consequently, we beat a hasty retreat to the meadow, returning quickly to the boat, and then the cabin for the night. No sooner had we gained the shelter of the cabin than the rain began.

And did it ever rain! Amazonian, jungle rains—throughout much of the night. As we fixed a good breakfast on the stove at first light, we were glad to see the rain had stopped. Overcast skies with a few hints of peach and persimmon on the horizon gave promise of an improving day. An hour later, we entered the same section of forest again, right off the big meadow, and quickly found the pink surveyor’s ribbon we’d left at the spot where our tracking had stopped the night before. Every leaf and piece of vegetation carried multiple water droplets just waiting to soak any passers-by. Every surface facing heavenward had been washed clean of all blood-sign, but our guide taught us both a new trick—one which really impressed me.

While Jack and I were struggling in vain to find a speck of red anywhere, the guide motioned for us to come over to where he was kneeling. When we reached him, he turned over a small leaf on a bush about three feet off the ground and pointed to a tiny drop of dried blood on the leaf’s dry underside. “How did that get there?” I asked naively.

The guide’s response was one of embarrassing simplicity. “The bear passed by this bush last night, and in doing so his body turned this leaf temporarily upside down.” I wondered why that had not occurred to me. It seemed so self-evident, once I thought about it.

Over the course of the next two hours, the three of us painstakingly advanced our hopes along the bear’s “trail”—from the stained underside of one leaf to the stained underside of the next—for perhaps 150 yards. At that point, we discovered where the bruin had made a bed and spent the night, or at least a part of it. The forest floor was all torn up, and we found one small blood clot lying there on the ground.

Picking up his trail from that point forward became much easier, though, because he had not continued his journey until everything was soaking wet—probably at daybreak. The grasses and ferns were freshly matted down wherever he had passed. First one log and then another gave up a few belly hairs where he had slid over their upper surfaces. There were, however, no further signs of blood to be found anywhere—neither on the upper or lower surfaces of any leaves, large or small. By 11 a.m., the sun was fully out, and as the warming afternoon began to dry things out, the grasses began standing up again. Our tracking job was rapidly becoming more and more one of divination. By two o’clock, the task had become impossible, and we collectively decided it was time to abandon the pursuit.

The grizzly had eluded his pursuers, and was clearly going to be a survivor—albeit one with a chip on his shoulder (or a broadhead, anyway). We all agreed he was likely to be one ornery customer for the rest of his life, whenever he might chance to have any further encounters with humankind in the future.

Nothing else about this 1969 hunt was memorable. It had, however, provided us both with our first, dangerous, close encounter of the furry kind. The kind of encounter that the fury of a furry grizzly (Ursus horribilis) could have turned horribly grisly. I returned home from that hunt acutely aware of my manifold blessings, both large and small. Life sometimes hangs by a thread—or sometimes by a bowstring.

Editor’s note: This article is the thirty-ninth of the BAREBOW! Chronicles, a series of shortened stories from accomplished hunter and author Dennis Dunn’s award-winning book, BAREBOW! An Archer’s Fair-Chase Taking of North America’s Big-Game 29. Dunn was the first to harvest each of the 29 traditionally recognized native North American big game species barebow: using only “a bow, a string, an arrow—no trigger, no peep sights, no pins—just fingers, guts, and instinct.” Each of the narratives will cover the (not always successful, but certainly educational and entertaining) pursuit of one of the 29 animals. One new adventure will be published every two weeks—join us on the hunt! You can learn more about the work and purchase a copy on Dunn’s site here. Read the thirty-eighth Chronicle here.

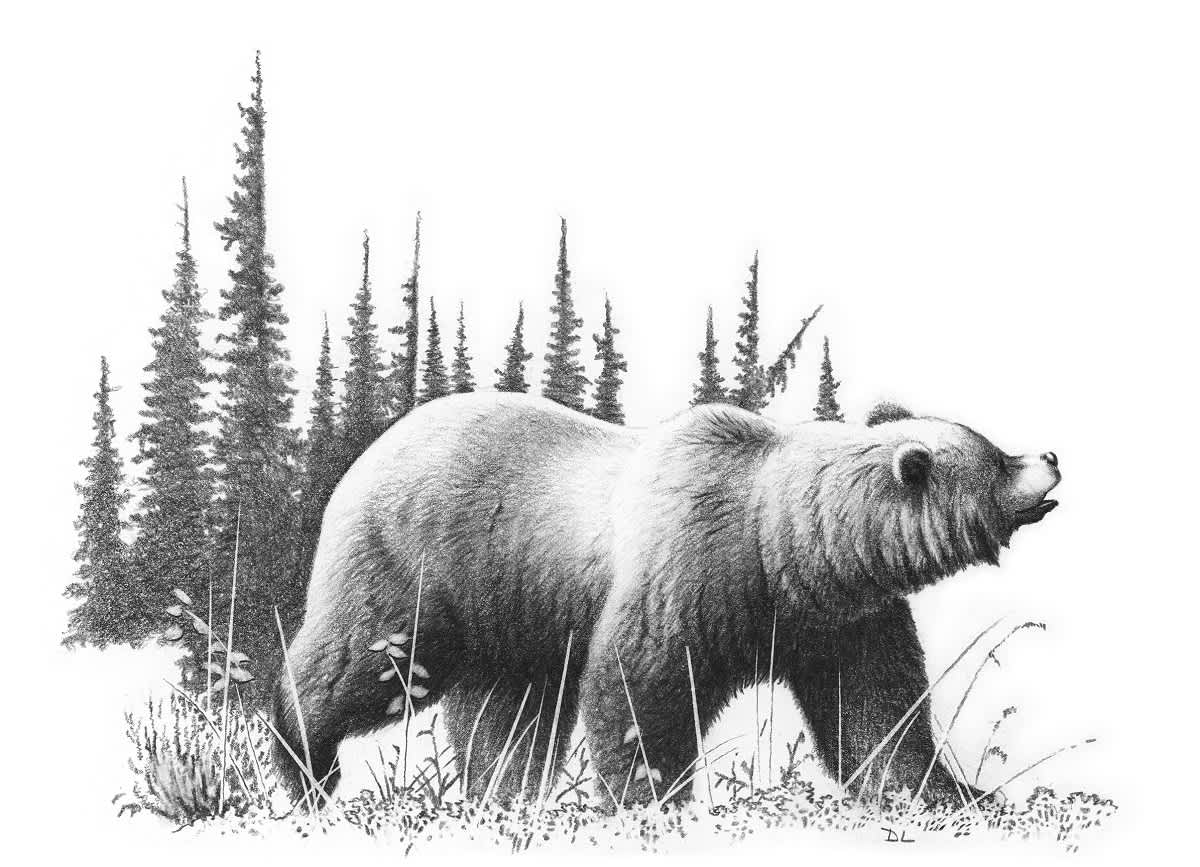

Top illustration by Dallen Lambson