History of: The AR-15

Jeff Williamson 05.29.18

The AR- 15 is at once beloved and vilified; a touchstone of America’s political bipolar condition on the subject of gun control and gun rights. The rifle design has been around for over fifty years and its history throughout has been anything but dull.

The popularity of the AR-15 is rooted in its association with the M-16 and M-4 variants which have been considered for service replacement more than once, yet to date have only received selected upgrades. Yet while all good things must eventually come to an end, another selection process is under way, even now. Though that program is not ready to discard the status quo, opting for limited alternatives at the squad level. Given the fact that the US is still involved in active shooting “conflicts” in more than a couple theatres, now may not be the best time for a service wide overhaul: the Marine Corps is not going for a full replacement with H&K’s M27 – a rifle that looks just like the M4, but is advertised to have better accuracy and a higher rate of fire (and price tag) – just a broader distribution of the new rifle.

What is clear, however, is that as long as the military variant of the AR remains in service, the civilian version’s popularity, and notoriety, will remain as well. A closer, even cursory look at the AR-15 suggests why the old gal may not be ready for retirement, just yet.

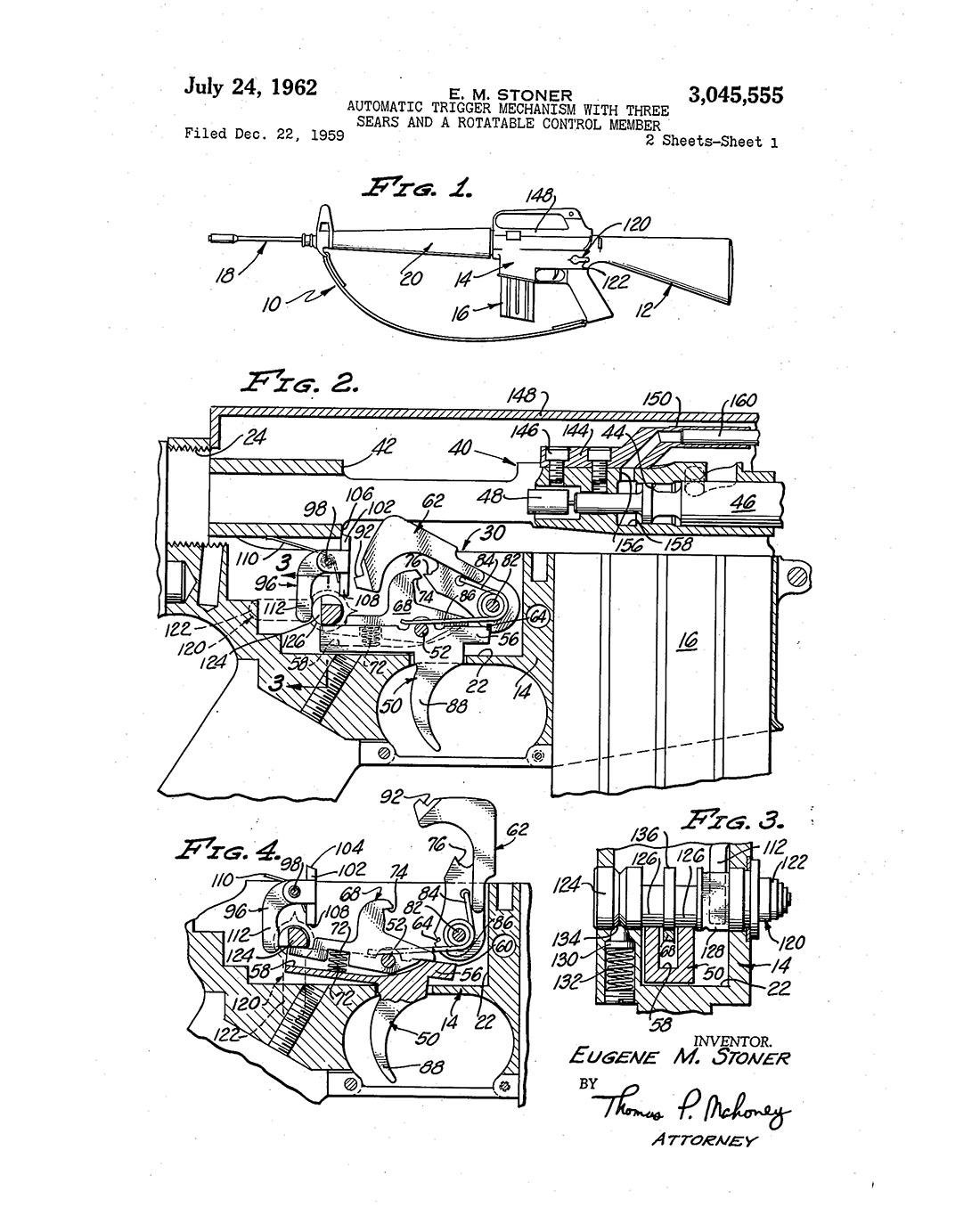

The AR15 rifle began life as an Armalite Rifle – that is what AR stands for – design in 1956 by Eugene Stoner. It was a scaled down version of the 7.62 caliber AR10, which was submitted to, but ultimately rejected by, the US as a replacement of the M1 Garand. Their choice fell to what is known as the M-14. Nonetheless, the US military saw the need for a smaller, lighter and more manageable high velocity round as a way for US soldiers to maintain fire superiority in the field: in the 1950’s field reports of the AK-47’s capabilities proved it could put out more rounds and the superior range of the M-14 was useless in the jungles.

Simultaneous to this was the development of Remington’s .223 round, and testing began on the scaled down Armalite Rifle Model 15. However, by 1959, facing insufficient production capabilities, Armalite sold the AR15 designs to Colt. By 1963, concerns in Vietnam along with reports that M-14 production was not up to the task to providing enough weapons led Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara to issue a halt to that rifle’s production. By that point, the US Air Force, along with several special forces units, had already been issued the AR-15 with select fire capabilities, in other words, the M-16. In typical McNamarian style, the Secretary of Defense made all armed forces adopt the new rifle: it was cheaper to manufacture, lighter, the smaller cartridge allowed for more ammo to be carried, and it was manageable when firing on full automatic. Where was the bad?

First, in order to provide enough ammunition in the new caliber, Olin Corporation changed the loads from ball powder to supplement the standard Dupont stick powder. It made no difference in the ballistic performance of the rifle, but it did create more fouling. This, coupled with a humid environment caused stubborn jams. Then add to the fact that Colt billed the weapon as self cleaning (even with the correct powder type, that is a bit grandiloquent) and encouraged soldiers not to worry about servicing their firearms. This resulted in quite a few dead GI’s found with disassembled rifles they were attempting to clear in the middle of a fight. It also was an albatross around the neck of this new rifle.

Quickly the US military amended their policies and ammo requirements. This included an initially dismissed as extraneous and costly feature: the forward assist to help manually close the bolt when the action starts gumming up: which can happen when the weapon is fired a lot.

To date, the M-16 has gone through many upgrades in the military, and the civilian AR15 has as well. Colt’s manufacturing capabilities were maxed out during the height of the Vietnam War, but gradually, as the war wound down, it was able to produce the civilian rifle. Throughout the 1960s into the 1970’s Colt serial number ranges show they produced somewhere on the order of 1500-3500 rifles a year. This was not a lot. In 1977, Colt’s copyright expired, and other manufacturers began production on a rifle that, on the surface, appears to not have been that popular. Mostly for Civilian Marksmanship Programs and the like, few shooters were attracted to the rifle. This changed over the next two decades

Many factors play into the massive expansion of the rifle’s publicity, but the media sensationalism doubtless plays no small part: intent on vilifying the rifle, it was cited as the weapon used in the 2013 Navy Yard shooting, even though the gunman used a shotgun and two pistols. AR type rifles of course were used in the 2017 Las Vegas Shooting and the 2012 Sandy Hook School Shooting. As well as by the 2002 DC Sniper. However, as far as national shootings are concerned, Federal statistics show that AR style rifles are used in less than 1% of all homicides. Of the estimated 11,000 people killed in gun violence in 2011, 322 people were killed by an assault style rifle, not even exclusively AR15 types. While both numbers are too many, the inspiration of the 1994 “Assault Weapons Ban” had perhaps little effect on crime, but an interesting effect on manufacturers as they altered designs to circumvent the law to bring products to market. Threats of a ban inspired demand for the rifle, as proven in 2013 after Sandy Hook.

Today virtually every major gun manufacturer (except Glock) makes an AR style rifle, as does a great many small gun makers and machinery manufacturers that obtained a manufacturer’s license. The popularity of 80% lowers further show how the threats of bans fuel interest in the gun and capitalize on the design’s modularity. It is important to note that making the receiver is not that difficult and all other parts are available via mail order since they are not parts that are registered. It should also be noted that federally, making a firearm is NOT illegal providing it is not made for sale and is not transferable. States have their own rules, however.

It is not hard to see why the AR is a popular choice for personal and civil use. Its light weight alone makes it ideal for small shooters, with a recoil that is more bang than push. It is effective. When properly cared for It is reliable. Most importantly, it is modular. Replacement parts and a relatively simple take down makes is a manufacturer’s and armorer’s cupcake making it a dream for field repairs: just swap out broken parts with the need for very few job special tools or much more than a bench vise. This has also led to a virtually overwhelming assortment of after market upgrades leading to the AR to be called either a Barbie or Lego gun for aficionados. A standard AR lower receiver can be made to fire a variety of cartridges from .22LR all the way to .50 BMG. As for optics, lights, lasers, handle configurations, imagination is the only limitation.

Downsides? Well for one, it is loud and “looks” mean. These are pretty much subjective complaints (it really IS loud). It does have tight tolerances: proper function requires care as the gas impingement system blows quite a lot of carbon back into the action which can cause jams. A piston system has been introduced that reduces the carbon build up, but that does not remove the need to clean the weapon.

Perhaps the biggest detriment to the AR15 to date is its media infamy. Yet that very eputation has kept the rifle at the forefront of sales right up to the 216 election. Production numbers throughout the first part of the 21st century show the gun’s popularity has not diminished until the “Trump Slump.” Threats of a loss of political power continue to keep gun rights activists and manufacturers mobilized.

The political future remains uncertain as the two dominant parties use every polarizing issue possible to fight for the hearts of voters. From a practical standpoint, the AR and associated industries are well entrenched in the US shooting world. It is unlikely that a collection ban will be attempted by any sane administration. But for as long as the M16 variants remain in service, demand for the AR15 type rifles will remain as well. Ironically fueled by media frenzy over the evil “black gun” as by practical utility.