Mid-Range AR Cartridges: .223 Remington, 300 AAC Blackout, and 6.8 Remington SPC

Tom McHale 12.09.19

Recently, a friend and I have been discussing “in-between” caliber options for the AR-15 platform. There are a plethora of proven options for close-range shooting with a light to moderate recoil tax. Think about the classic AR-15 chambered in .223 Remington and the 300 Blackout. There are also great options for long-range shooting too. 6.5 Creedmoor, the Grendel, and the new .224 Valkyrie come to mind. There are others, but you get the idea. As for the “in-between” solutions that can effectively reach out past 500 yards, but without all the boom and thump of something like as .308 AR-10, what should one consider?

Of course, the answer largely depends on your intended purpose. Are you hunting? Punching holes in paper? Are you ringing steel for fun? Or are you knocking over steel silhouette targets? The big differentiator is downrange performance—do you need adequate foot-pounds or momentum hundreds of yards downrange or not? Most everything has impressive kinetic energy at the muzzle, but far fewer standard AR cartridges maintain a useful amount of “oomph” far downrange.

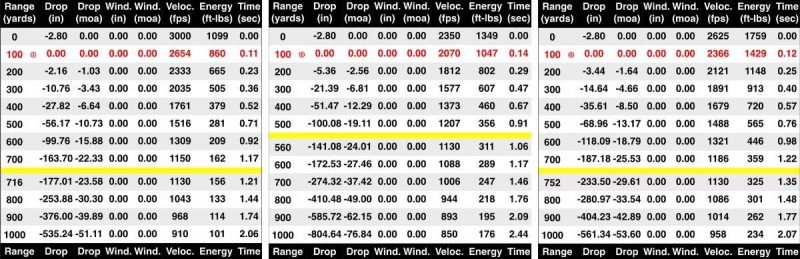

Then there’s the question of bullet drop over distance. Technically, drop doesn’t matter. These days with a little knowledge, a ballistic calculator (free options are plentiful), and a decent scope, you can hit distant targets with boring consistency. Gravity is categorically predictable. There are two catches in the bullet drop world: the supersonic to subsonic transition zone and the limitations of scope adjustment. When bullets slow down from supersonic travel (about 1,130 feet per second where I shoot) to subsonic speeds, their performance becomes much less predictable. The other gotcha is that while a drop of 20 inches or 200 doesn’t matter in theory, scopes can only compensate so far until they run out of adjustment. That’s why people use compensated rails and scope mounts for extreme long-distance shooting.

Let’s consider some examples.

.223 Remington

The .223 Remington cartridge in its 55-grain “standard” configuration delivers 1,108 foot-pounds of kinetic energy at the muzzle. If you were concerned about downrange muzzle energy, you’d fall through the 500-foot-pound barrier at about 325 yards. By the time it goes subsonic at 710 yards, it’s only carrying 163 foot-pounds of energy. That’s about the same as a 73-grain .32 ACP bullet at the muzzle and not too much more than a Nolan Ryan fastball pitch, which works out to 128 foot-pounds.

As for bullet drop, that light 55-grain bullet falls about 15 inches at 325 yards and 170 inches by the time it goes subsonic at 710 yards. That’s over 14 feet and requires a 23 minute-of-angle scope adjustment.

300 AAC Blackout

As an avid reloader, I love the 300 Blackout. I really do. You can do almost anything you want with it, ranging from lobbing 240-grain bricks to zipping 110-grain supersonic, low-drag projectiles. And it all works with only a barrel change. Magazines, receivers, and bolts are compatible—only the bore has a bigger hole. And Blackout uses cut and reshaped .223 Remington brass, so the supply of cartridge cases is cheap and unlimited.

From a mid-range ballistic perspective, the supersonic version has some advantages over .223 Remington. Using the Barnes 110-grain VOR-TX Tipped TAC-TX load, it delivers 1,349 foot-pounds at the muzzle when velocity is 2,350 feet per second. Given the limited case capacity of the design combined with a fatter .308 bullet, it does tail off faster than .223 or 6.8 SPC. This round will go subsonic at about 555 yards where I live and be carrying 318 foot-pounds at that point. Also, by that point in its flight, it’ll have dropped about 135 inches or about 11 feet.

The net-net of 300 Blackout is that it’s a great shorter range, say zero to 300-yard option. Sure, you can shoot it at longer distances, but if you’re hunting or ringing small steel targets, it’ll become less predictable (and powerful) the farther you go.

6.8 Remington SPC

The 6.8 Remington SPC has a bullet weight sweet spot in the 90 to 115-grain range. For our example, let’s consider the Remington 115-grain Premier BTHP Match load.

While not a long-range specialty cartridge, the increased bullet weight makes a big difference in terms of downrange energy. At the muzzle, this load delivers more than 1.5 times that of the .223 with 1,759 foot-pounds of kinetic energy. Better yet, it carries that energy over distance. If we use the same 500-foot-pound threshold as the .223 Remington, it doesn’t get there until well past 500 yards. For hunting, if we use a common medium-sized-game energy threshold of 1,000 foot-pounds, the effective range of the 6.8 SPC is about 250 yards, at which point muzzle energy dips into three-figure territory.

As for bullet drop, the trajectories of .223 Remington and 6.8 Remington SPC are very similar, although the heavier 115-grain bullet of the 6.8 load drops a hair faster. When the 115-grain 6.8 SPC bullet transitions to subsonic flight at 751 yards, it’s dropped 231 inches. That’s about 19 feet, or 29 minutes of angle if you measure that way.

What 6.8 SPC Requires

In the AR platform, you’ll need a new barrel with an appropriately shaped chamber and larger hole in the bore. The bullets measure .277 inches, not coincidentally the same as the .270 Remington. As we’ll discuss in a minute, that a big deal if you choose to reload.

The cartridge case is derived from the .30 Remington—it’s not a reworked .223 Remington case as with the 300 Blackout offering. That means two things for you. First, case capacity is larger than that of the Blackout. With a bullet size somewhere in between that of .223 and 300 Blackout, you’re not eating up limited case space with excess bullet diameter and length. That’s part of what drives improved downrange performance with a heavier bullet. The second factor relates to capacity. The case is larger in diameter than a .223, but again, it’s a moderate increase, so capacity in a “standard” AR magazine is 25 rounds. Note that magazines for 6.8 SPC are tweaked for reliable feeding, so while they fit in the same sized magazine well, they’re not interchangeable.

Last, you’ll need a 6.8 SPC bolt to accommodate the larger case size. That’s fairly easy to accomplish.

All in all, we’re looking at a larger cartridge offering in a standard AR upper and lower receiver. Subcomponents like the barrel, bolt, and magazine are unique. The important factor is that unlike other larger caliber offerings like .308 and 6.5 Creedmoor, the 6.8 doesn’t require the enlarged AR-10 receiver components.

Ammo

One of the reasons behind the development of the 6.8 Remington SPC was to improve terminal performance out of short barrel carbines. When .223 / 5.56mm barrels start to shrink from 16 or 18 inches to 10 or 12, velocity falls off—a lot. The .223 works pretty well when humming along at 3,000 or more feet per second because it tumbles and fragments. At slower speeds from shorter barrels, it’s more likely to make small holes. Using the larger .277 bullet in front of a full cartridge case full of propellant gives you a better ballistic outcome at reduced velocities.

If you’re a reloader, there’s a hidden benefit to the 6.8 SPC. You can find .270 Remington projectiles everywhere. During the great reloading component and ammunition shortage under a previous administration, I couldn’t get my hands on .223 or 300 Blackout (.308) projectiles to save my life. On the other hand, .277 bullets were everywhere in all sorts of styles. Were they ideal for the 6.8 SPC? No. Were they perfectly serviceable? Absolutely.

The Net-Net

I really like the 6.8 SPC cartridge. I’m not going to argue that it’s better or worse than caliber X, Y, or Z. The .223 and 300 Blackout have their places, and for shorter range use, I’ll happily choose either in a heartbeat. But if you want to reach out a bit farther, and with a bit more authority, take a look at the 6.8 Remington SPC.