The BAREBOW! Chronicles: When Push Comes to Shore

Dennis Dunn 05.15.14

In 1994, I had returned to Mackay Lake Lodge with my wife, Karen, and my two sons, Bryant and Reagan. It was their first visit to the Northwest Territories, and it was a great family hunt that produced quality, trophy caribou bulls for both the boys—but not for their dad. I did harvest a small bull on the final day for meat, but its antlers were singularly unimpressive.

My third hunt at Mackay Lake was made in 1996 with Duane Smith, a good friend from Williams Lake, British Columbia. I was still living in Vancouver at the time, and we decided we’d make the long drive to Yellowknife and take in the glorious fall foliage along the way. Once we left the Alaskan Highway west of Fort Nelson and headed into the Territories, the colors changed from special to spectacular. As we bypassed Fort Simpson and continued toward Fort Providence, the golden birches, aspens, and cottonwoods transitioned from simply spectacular to utterly sensational! Three days of driving finally brought us into Yellowknife on the third evening. The last day had treated us to an especially buggy crossing (by ferry) of the Mackenzie River, as well as numerous sightings of the relatively scarce wood bison.

The next morning, Gary Jaeb of True North Safaris had us flown in to his base camp at Mackay Lake. He had built a long airstrip right next to his lodge so that he could use a larger aircraft to transport a larger number of hunters at one time. My recollection is that the plane which flew Duane and me into the bush (plus 10 or 12 others) was an old DC-3 from World War II.

Because I was hopeful the caribou would be as plentiful around the lake as they had been on my previous hunts, I made the decision to bring with me only a recurve bow. It was an old take-down model made by Bear Archery that pulled 46 pounds at my draw, and I figured it should be sufficient for any bull caribou. Such proved to be the case, in fact, and by the end of our week at Mackay Lake the recurve had allowed me to fill both my tags with the harvest of two very nice bulls—one of them of true trophy quality. In the four years that had passed since my first hunt with True North Safaris, I had really spent some serious time studying the Pope and Young Club’s scoring sheet for caribou, and those hours finally paid off handsomely.

***

Duane, however, was the first to score. He had brought two bows with him from home: a brand new compound and the trusty recurve with which he had learned to shoot. Our first day out in the field, Duane missed an enormous bull with his compound. Quite disgusted with himself, he decided to hunt the rest of the week with his recurve. He felt much more confident with that weapon in hand, so it was clearly the right choice for him at that time.

Two days later, everything came together perfectly for him. We had crossed the big lake and hiked inland about a mile, accompanied by our Inuit guide, Leon. Caribou seemed to be everywhere; dozens upon dozens came streaming over the nearby hill in our direction. Two minutes could not pass without a new band of half-a-dozen to two dozen caribou showing themselves on some skyline close at hand. Often we would see only the tall antlers of several bulls trotting along in single file along the back-side of a rocky rib. Moving antlers without heads is a sight to behold!

It suddenly dawned on me that all the traffic was flowing in one direction only. This was it! This was the migration! This was the annual phenomenon one always hears about, but which very few humans get to witness in person. Duane and I were right in the thick of it, and for two days we must have seen 5,000 caribou migrating all around us along the shores and over the ridges above Mackay Lake. I had never seen anything remotely like it, before or since.

It was on the third morning of our hunt that Duane made a truly amazing shot with his recurve. A sizable group of cows, calves, and bulls was trotting past us to only-God-knew-where. The unique clickety-clicks of their ankles were creating a subtle symphony of sound against the backdrop of a windless autumn day. One especially handsome bull with outstanding “tops” brought up the rear and veered slightly closer to Duane than the others. He was trucking along, and my friend had almost no time to draw and get a shot off. In fact, Duane didn’t even take the time to raise his bow to a vertical position. As the animal sped past, he simply shot “from the hip” (his bow horizontally parallel with the ground), and sent the three-blade Savora broadhead I’d given him right through the heart of the unsuspecting bull. We later paced off the distance of the remarkable shot at 33 yards.

I had been standing about 80 yards from Duane when he released his arrow. A few seconds later, his trophy-class caribou did a death spiral and died at my feet. It was all over within 30 seconds. Congratulations flew fast and furious, and I don’t think Duane wiped the ear-to-ear grin off his face until he fell asleep that night.

My own “hunter’s luck” kicked into high gear the next two days: first, with the taking of a bull that came within an eyelash of making it into the Pope and Young records, and then with the harvest of a true Boone and Crockett animal. It was the second bull whose harvest gave rise to the title of this story.

***

It was one of those blustery days when the outfitter has a tough decision to make as to whether he lets his guides and hunters leave base camp in the morning by boat. Mackay is a huge lake, and during a storm it can start behaving like an ocean. Waves eight to 10 feet tall can end a hunt in a hurry, if your guide in the back of your small aluminum boat is not a skilled mariner—or if God is not watching over you as the preferred Skipper-of-Choice.

Though one of those marginal days at the outset, the weather started showed promise of improvement. Thus Gary gave us all the green light to go exploring the lakeshore. Leon had in mind to hunt a long inlet on the opposite side of the lake, not far from Gary’s Warburton Bay Camp. We must have traveled at least 30 miles up the lake before we finally gained the much calmer waters of Banana Bay. Fortunately, we’d been going with the wind, so the incessant pounding of the boat had been rather muted and cushioned. We knew the trip back to camp that evening was likely to be far different.

On that particular day, we were not seeing anything close to the numbers of caribou we’d seen on the several preceding days. As a matter of fact, very few were showing up, and once we reached the end of the bay by early afternoon, we decided to strike out on foot. The hike on solid ground was most welcome, yet it took a couple of hours before Lady Luck came knocking. Suddenly, three bulls slowly crested a ridge, feeding our way with heads lowered, and each pushing an impressive rack in front of them that looked much like the scoop on a front-end loader. They were, at most, 250 yards distant. One in particular appeared impressively tall, wide, and handsome.

As there was no cover anywhere around more than 12 inches tall, Duane and Leon urged me to go after them by myself. They immediately laid down on the ground to watch the action. There were precious few contours in the terrain available to help close the distance between me and the feeding bulls. Pushing my bow in front of me, I began slithering their way on my belly—but only when all three had their heads down at the same time. This stop-and-go crawling technique exhausted its viability once the last, helpful landscape feature had been utilized to the fullest. When the bulls finally decided to take a late-afternoon siesta, I was pinned down completely, still 80 yards away.

For nearly three-quarters-of-an-hour, the drama was at a standstill, but that didn’t mean I was bored! Lying flat on my stomach, I found it fascinating to glass the three sets of antlers and compare the many substantial differences. The big, trophy bull clearly “had it” over the other two in every department, and I kept having to wipe the drool off the bottom of my chin. His rack was almost four feet wide, and I knew he was very likely a Boone and Crockett bull. When the trio finally rose to their feet, they did not resume feeding, but instead began traveling obliquely toward me.

Since I was totally exposed, I considered it too risky even to lift myself off the ground until the biggest bull was within bow range. As he began to pass me by at around 30 yards, I struggled to my knees and raised my bow-arm to draw. The movement, of course, caught his attention instantly, and he paused momentarily to look in my direction. I completed drawing the arrow shaft, and—just as it left my recurve—the bull went into motion. Instead of striking the rib cage I’d been aiming for, the missile struck him in the hip. Whereas the two other bulls exploded out of there, hell bent for the Yukon, my bull—much to my surprise—simply turned and started walking slowly downhill toward the water some 500 yards away.

Duane and Leon had seen it all from less than 100 yards, and they quickly joined me to watch the stricken bull and see how the drama would play out. I felt that almost certainly my broadhead had severed the femoral artery in his hip, and that it was now only a matter of time. When the stately animal at last reached the edge of the bay, he waded in and crossed over to a small island. Exiting the water, he walked across to the far side and lay down. The situation demanded an immediate powwow with Duane and our guide.

“Leon,” I started off. “The way he’s acting, I suspect I got one or both of his femoral arteries. If we just leave him alone for a while, I think he’ll probably expire right there in his bed.”

“I’m afraid we don’t have that kind of time,” replied Leon. “We need to finish him off quickly. Otherwise, with the high winds still blowing from the east out on the lake, we’ll have to spend the night here—or else run the risk of a boating accident trying to get back to camp in the dark.”

I acknowledged that those alternatives didn’t seem all that attractive and began contemplating other possible options. Duane suggested we head for the boat and then put me on the shore-side of the little island. Leon nodded his assent, and we all took off for the tiny speck of a boat we could discern, snuggled up against the near bank.

Fifteen minutes later, as we approached the part of the island farthest away from the bedded bull, he was nervously watching us. When I stepped out of the boat onto the sand, he rose and began wading out into the lake straight away from me. The distance was then around 50 yards. Once in the water up to his belly-line, he turned broadside to look at me, and I released an arrow which entered the flat surface of the lake about three feet shy of his ribs. Unfortunately, no contact occurred. A second and third arrow sailed harmlessly over his back as he started swimming away from me, across the bay toward the far shore. I hustled to get back in the boat, so we could get in front of him before he reached dry land on the other side.

After letting me out once again, with the bull swimming right toward me this time, Leon motored off out of the way to watch the conclusion of the drama. It was clear that the bull was very aware of my presence on the shore. Since there was absolutely nowhere to hide, I just stood there waiting for him. About 60 yards out, he swerved and began swimming in a different direction toward another part of the bank I was on. I adjusted my position accordingly, and he readjusted his line of travel again. Much concerned about the onslaught of evening, which was waiting for no man or beast, Leon started using the boat—from a distance—to put subtle pressure on the tiring swimmer to come ashore in my vicinity. Before long the predestined outcome had run its course, and a final arrow pierced both lungs as the noble animal gave up his life standing in the shallows of the lake.

The way the drama ended made me sad, but the bull probably died sooner than he would have, had we left him alone on the island. Once a hunter wounds his quarry, he has a moral obligation to finish him off as quickly as possible. Leon knew what he was doing, and I could not fault him for using the boat the way he did, to nudge the bull in my direction. It meant, however, that the magnificent trophy could not be entered into any records book. All hunters seeking to enter an animal must sign a Fair Chase Affidavit, stating—among other things—that no motorized vehicle or watercraft has been used in the taking of the game. I knew my first arrow had been strictly “fair chase,” but I knew the second one, though humanely necessary, was problematic. When “push had come to shore,” the records-book was a non-issue. The only thing that mattered was doing what had to be done, as rapidly as possible.

It took all the combined strength of Duane, Leon, and myself to haul the heavy bull out of the water and up onto the bank for the hasty butchering job which our guide managed to complete in fewer than 20 minutes. In another five, we had the four quarters of meat, plus the hide and the antlers, all loaded into the boat, and we took off for camp as dusk and a thick cloud-cover began to settle over the gray landscape. Reaching the main body of the lake, we found the high winds and waves Leon had feared, and the trip “home” that night proved to be a long, wet, frightening, and psychologically-exhausting rodeo.

Months later, out of curiosity, I measured my bull’s antlers with the Pope and Young scoring system. The 42-inch-wide, inside-spread between his main beams, together with the heavy palmation on top, contributed greatly to the net score of 355. The minimum for the species is 300, so I allowed myself to be thrilled by that—knowing in my heart that, with more daylight available, the animal would have been recovered, anyway (even without the “use” of the boat for nudging purposes). It was truly a great hunt Duane and I had shared together, and one I shall never forget.

Editor’s note: This article is the twenty-third of the BAREBOW! Chronicles, a series of shortened stories from accomplished hunter and author Dennis Dunn’s award-winning book, BAREBOW! An Archer’s Fair-Chase Taking of North America’s Big-Game 29. Dunn was the first to harvest each of the 29 traditionally recognized native North American big game species barebow: using only “a bow, a string, an arrow—no trigger, no peep sights, no pins—just fingers, guts, and instinct.” Each of the narratives will cover the (not always successful, but certainly educational and entertaining) pursuit of one of the 29 animals. One new adventure will be published every two weeks—join us on the hunt! You can learn more about the work and purchase a copy on Dunn’s site here. Read the twenty-second Chronicle here.

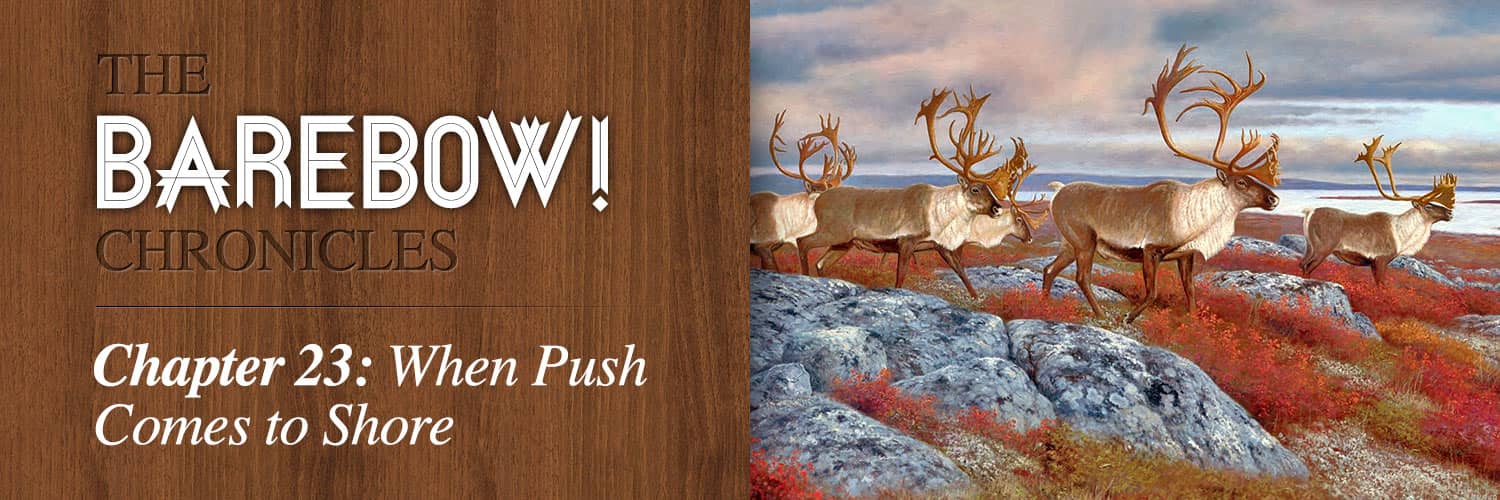

Top illustration by Hayden Lambson