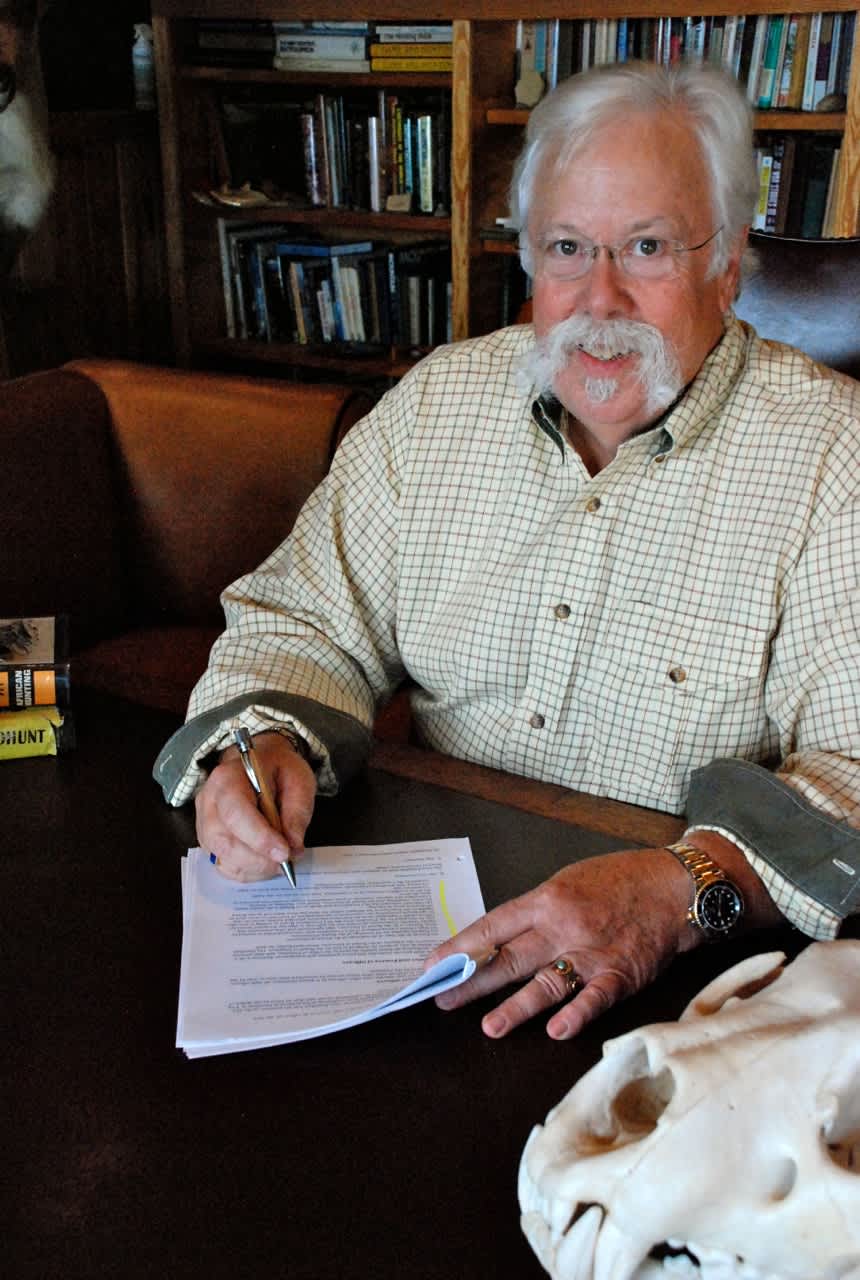

Leaders of Conservation: SCI Foundation President Joe Hosmer

Daniel Xu 04.17.14

This interview with Safari Club International Foundation President Joe Hosmer is part of OutdoorHub’s Leaders of Conservation series, in which we sit down with leaders of the North American conservation movement to learn more about the stories behind their organizations and people.

In 1972, two safari clubs—one in Los Angeles and one in Chicago—decided to join up and create Safari Club International (SCI). Over the next four decades, SCI reached out to independent safari clubs across the globe to combine sportsmen in an unified organization. Many people think it was during this time that the Safari Club International Foundation, the conservation branch of SCI, split off from the original organization. Joe Hosmer, president of the SCI Foundation, said that’s not exactly accurate.

“SCI Foundation is the original entity,” Joe shared. “We later created another organization which we also gave the name Safari Club International, and the original club became SCI Foundation.”

The problem of having similar names is that, of course, many people tend to get the groups mixed up. But the goals behind the organizations are self-evident.

“That is the easiest question we get,” Joe said.”SCI is ‘First for Hunters’ while SCI Foundation is ‘First for Wildlife.’ The Foundation is the other half of the equation, and our mission is wildlife and wildlife conservation.”

Although they are different legal entities, Joe said the partnership between the two groups is a harmonious one.

“You’re not going to have hunters unless you have wildlife and you’re not going to have wildlife unless you have good conservation practices.”

Joe is a 15-year veteran of SCI Foundation, spending 10 of those years in the group’s conservation committee. To many, Joe was the obvious choice when he was selected as the Foundation’s president in late 2010. A lifelong hunter and conservationist, Joe also brought the skills he learned from a successful career in the telephone industry.

“It began many, many years ago when I got out of college,” Joe started with a chuckle.

He had followed in his father’s footsteps and went into telecommunications, rising through the ranks and ending up in places like Central America and West Africa as a design and engineering contractor. While training personnel in Liberia, Joe decided to start his own company.

“Twenty-eight or 29 years later, that little corporation had 500 engineers on each continent,” Joe said.

He eventually traded the corporate office for fieldwork.

“At an SCI meeting I raised my hand one time and said, ‘Jeez guys, I sold my company so I got a little time on my hands. Is there anything I can do to help?’ Somebody asked me if I did a lot of work overseas and I said yup. They asked me if I was used to dealing with foreign governments and protocols and I said yup again.

“The next thing I know my wife’s telling me I was away from home almost more than I was at home. I was traveling all over for SCI over wildlife issues, conferring with experts and biologists.”

When he was the Foundation’s Conservation Chairman, Joe and Dr. Bill Moritz led field teams to Tajikistan for sheep surveys in early 2010. The Foundation’s focus was on the region’s argali sheep, also known as Marco Polo sheep. Driving Toyota Land Cruisers at an elevation of 17,000 feet, the team conducted sheep counts and calving studies in partnership with the Tajik government. Due to decades of wild sheep management, Tajikistan has the world’s highest concentration of argali sheep and a remarkably stable population. A significant portion of the conservation funds used to protect these animals from threats like poaching or habitat loss comes directly from hunters. However, Tajikistan halted hunting of the animals in 2008 and 2009 despite a minimum population of 24,000 wild sheep. Ironically, this move threatened to remove the protections that the argali sheep enjoyed.

“The establishment of game management areas that provide trophy animals have ensured the survival of wild sheep and other mountain wildlife,” wrote sheep expert Dr. Raul Valdez, who accompanied the SCI field teams. “In these areas, wild sheep are protected from illegal hunting and domestic sheep are managed in coordination with wild sheep to avoid overexploitation of the forage resource.”

As a result of the SCI Foundation team’s surveys, the Tajik government reallowed hunting of the argali sheep.

“That was one of my fondest successes,” Joe said.

For the last three years, the Foundation has sent teams to Tajikistan twice a year to ensure the health of the argali sheep. With 60 landmark conservation projects, Joe intends to lead the Foundation through one success at a time.

“One of my goals for the SCI Foundation is for the organization to mature to the point where it will be recognized as the leader of the hunting community and sustainable wildlife conservation,” Joe shared. “It’s a lofty goal, but it’s one we find ourselves closer and closer to every day.”

But he still finds time to travel and hunt. Later this year Joe will be returning to the high altitudes of Central Asia, but his vehicle of choice will be a little bit different than the last time he went.

“In addition to being an avid hunter and conservationist, I’m also an enthusiastic motorcyclist. I have the opportunity to travel to the Himalayas for three weeks this May, so I’ll be crossing the mountains on a Triumph motorcycle.”

And this time, he won’t have to count sheep.

We would like to thank Joe for taking the time to talk with us. For more profiles of leaders of conservation, please read our recent interview with NWTF CEO George Thornton.